The Mad Agriculture Journal

Mycelium: Nature’s Recyclers

Published on

January 16, 2025

Words by

Zach Hedstrom

Interview by

Jonnah Perkins

Photos by

Beau Dahler

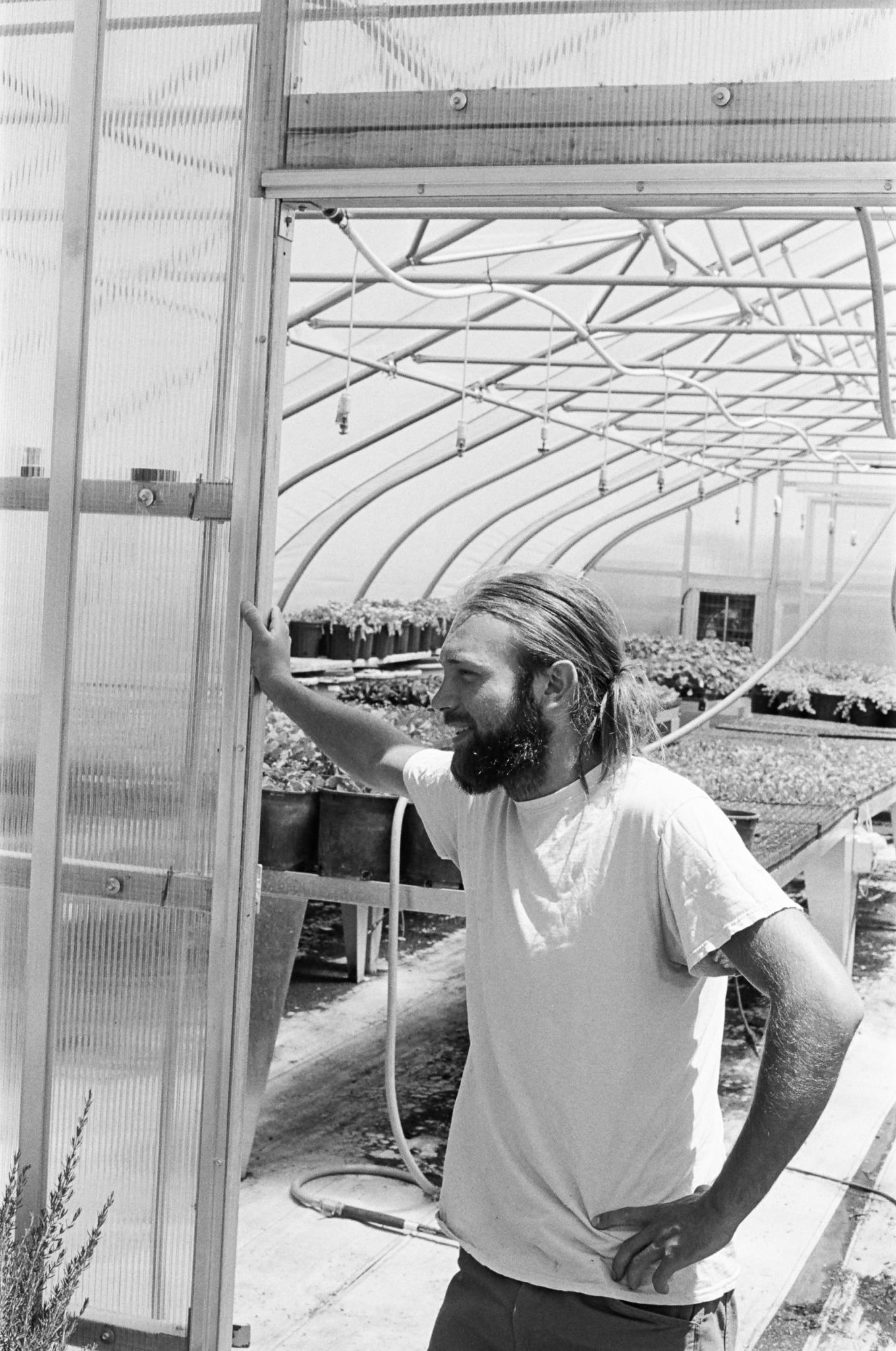

Zach Hedstrom’s journey of leading Boulder Mushroom is as deeply philosophical as it is grounded in practical science. This past summer, Mad Agriculture’s Director of Media, Jonnah Perkins, traveled around Boulder County with Zach, documenting his transformative approach to fungi and regenerative ecosystems. From a modest one-room cabin in Fourmile Canyon, Zach’s venture has expanded into a movement that brings together mushroom cultivation with visionary agricultural and forestry practices across Colorado’s landscapes. Rooted in a profound respect for nature and community, Zach’s work harnesses the unique powers of mycelium to regenerate soil, restore water resilience, and transform local waste streams. Asked to describe the motivation behind his work, Zach didn’t send us a standard mission statement—he sent a poem.

As above is below —

Bunches of grass, timid

Dancing aspen, creeping moss

All emerging from the unseen depths.

Brushstroke clouds on pale blue,

Cantankerous nebulae in the black ether.

Webs of dark matter throughout

The expanding cosmos defies understanding-

By even the strongest minds of our generation.

The ethereal unknown, unseen workings of universal flux,

The power below and above, within, upon,

Undisclosed.

Mycelium is unseen power —

Like wind, like gravity

Like one’s longing for connection in a fragmented world.

Decomposition = fertility

Inherent unity between the fallen and the emerging new.

Life upon life, cycling …

Look around and witness a great demise.

Dry cracked earth for miles on end,

Water with iridescent skin of chemical poison,

Drought and flood,

Subsidy food sold from plastic shells,

Acres of glyphosate soaked GM corn, not for human consumption —

Feeding the world?

This great expanse of friendly earth, punished

By a heavy hand that rules by force and is

Governed by the cruel plutocratic profit machine.

The human condition — fraught,

Desperate, isolated, caged, broken, yet

Longing for an abundant future crafted from dreams

Of what could be. Can it?

Eruption out of decay is the Way of Truth.

Inspired minds blink twice and peer through dense smog,

The intellect of the Greater Mind, the Collective,

Tuning the antenna to contribute a word, an idea.

The ‘crazy’ ones may pursue unconventional ideas,

Challenge the status quo, but they know

That somewhere a star is exploding into a supernova and

There is much more to our world than meets the eye.

Therefore, as soil is created through magical transformation of the Fallen,

So too may richness and fertility be crafted through transformation, genesis.

The tortured Earth may receive medicine, good food, a warm bed.

The dormant seeds hiding below may arise, and

Wisdom may germinate in our hearts and guide us

Towards the future that we have dreamed of.

Mycelium is the inventor, the chemist,

The recycler, the healer, the connector,

The destroyer, the mother,

The hidden magician, the medicine of earth,

The interstellar energy of the underground,

The ally.

Our world is contaminated. Toxic.

Soils are dry and barren, forests deteriorating.

As we ask ourselves, ‘How did we get here?’ and ‘What now?’

One may take pause and look into the unseen world below.

There may just be some answers underfoot.

Jonnah:

Can you take us back to the inception of you starting Boulder Mushroom? What was the emotional urgency in you to create this business?

Zach:

I started Boulder Mushroom in 2020 out of a one-bedroom cabin in Fourmile Canyon where I’m still living today. Boulder Mushroom has very, very small humble roots. I joined the Colorado Mycological Society (CMS) when I was 15. I grew up here in Boulder and got interested in foraging and mushrooms. When I joined CMS over a decade ago, mushrooms hadn’t really become quite as popular as they are now. It was a lot of really interesting, quirky, eclectic, older individuals that had been dedicating their lives to this sort of fringe scientific field.

A lot of folks were excited, and took me under their wing, and got me really interested in the field of mycology at a young age. I remember going out on field days forays, and having lessons from older mycologists, things like, “Oh, the way that you know what a Russula is, you take it and chuck it against a tree and it explodes into a million pieces.” And it felt like this really tantalizing, interesting world that I hadn’t been exposed to. The experience of being out in the wilderness in nature relating with the environment instead of just being an onlooker was super cool to me.

I was also quite interested in regenerative agriculture, and natural farming and foraging from a pretty young age. I worked with companies like MASA Seed Company, sorting seeds and cleaning seeds, and growing gardens in Boulder as a high schooler where I learned how to manage a small scale market garden.

The interest in mushrooms and mycelium and mycology just kept presenting itself as this central piece in my life. I began teaching workshops at a local nursery here in Boulder when I was 17 years old then I started to guide mushroom forays. Taking that leadership sparked this inspiration in me to start my own company.

While teaching mushroom growing classes, folks would ask me, Where do I get my mushroom spawn? I’d refer them to companies in Washington, Maine, or Oregon. Yet simultaneously I was really interested in this bioregional agricultural movement, and reading a lot about local seed banks, and local seed stocks. I put two and two together in my mind and realized I’m teaching about this crop, growing mushrooms, and then I’m telling people to go and get their seeds from this location across the country. The main reason that I started Boulder Mushroom was to be a regional spawn provider in the State of Colorado and the Mountain West.

Then things took off really fast from there a little bit unintentionally. My neighbor came over one day and walked into my cabin, and saw every shelf that I had in my tiny cabin just overflowing with blocks of mushrooms and petri dishes, and a fridge where my shoe rack should have been, that was full of petri dishes. He started asking me a lot of questions, and then he offered to let me use his basement which was vacant, as a shop space. That was my first step out of the one-bedroom cabin.

There was a lot of interest in the work I was doing with native strain and cultivation. That was something that we did from the beginning–going out into the wilderness and getting these local strains, and bringing them into cultivation. That resonated with a lot of folks in the area that wanted to do fungal composting but didn’t have access to native strains.

That was when the momentum started to pick up. This was also when we also got our first grant through Boulder County Sustainability Office to do a very small scale pilot project of decomposing farm biomass with mycelium. The results of that were quite good, showing that the biomass could successfully degrade and that mycelium could help the landscape hold more moisture. That project catapulted us to start working with other organizations like Eco-Cycle, and The Watershed Center, and some of the other farms in the Boulder County area.

I started the business in 2020, and by 2022, it was obvious that we needed to step it up and turn this into more of a full-scale operation to meet the needs that were being presented to us. That’s when we moved into our current facility and started to get more serious about doing the native strain cultivation, learning how to cultivate larger quantities of mushroom spawn, and partnering with local governmental organizations and nonprofits.

Jonnah:

Can you unpack the science inside of mycelial composting and how spawn catalyzes that process?

Zach:

Fungi are nature’s recyclers. The saprophytic fungi have the capacity to chemically disassemble all different kinds of organic matter into simpler compounds that ultimately release plant-available nutrients. Mycelium is the vegetative structure of the organism that produces mushrooms. Mushroom spawn is just live mushroom mycelium in some kind of a carrier. Oftentimes it’s a carrier of sawdust or grains, but it can also be a liquid. Essentially when you introduce mushroom spawn, you’re introducing mushroom mycelium. Mushroom mycelium catalyzes an enzymatic digestion process of the organic matter. In this region, we have a large proliferation of wood waste from fire mitigation, and that wood waste takes quite a long time to decompose through natural processes because of lignin and cellulose. These two structural components within wood are chemically very, dense,which is what makes wood so difficult to degrade, especially in an arid climate.

When we introduce mycelium, and mainly the wood-rotting saprophytes into wood, then the enzymes that are produced by that mycelium are able to systematically digest and disassemble all those chemical constituents in the wood that make it intact and dense, and hard to break down. That can take place in compost as well. In food scraps, in nitrogen waste like manure. It just so happens that out here, we have sort of an overproliferation of carbon-based biomass in our waste stream from forestry that is a little bit challenging to deal with at a large scale.This is where mushrooms and wood decomposing fungi can really come into play to help turn that waste product into an asset.

Jonnah:

You have worked quite a bit in fire mitigation. Can you talk about how having a robust mycelial community suppresses wildfire?

Zach:

A healthy forest ecosystem has a huge amount of fungal diversity within the soil, fungi that form symbiotic relationships with living trees to help make those trees more resilient and robust, as well as a number of saprophytic fungi that help to recycle the wood which falls onto the forest floor, as well as pine needles, pine cones, animal manure, and plant roots. So there’s a carbon cycling system within the forest which is deeply integrated with the biological system, and particularly the microbiological system. One of the things that is a part of the forest carbon cycle is fire. Meaning that, it is normal and natural for wildfire to move through a forest, and take some of that carbon, and convert it into ash and smoke in a properly functioning ecosystems.

That being said, due to human management of forests, as well as the encroachment of human civilization into forest ecosystems, the last 150 years or so have shown a legacy of fire suppression, at least in this region. Meaning that, the wildfires that would naturally burn have not been burning. That means that there is a denser profile of tree growth within our forest ecosystem than normally would be the case. That extra dense fuel load within the forest leads to a heightened fire risk, and a risk of much more intense, destructive, hot, mega wildfires.

Traditionally speaking, in a naturally functioning forest ecosystem where fire is present, fire might burn undergrowth, it might fully burn some trees, but a lot of the trees in our ecosystem are actually quite fire resilient. So that fire often wouldn’t fully kill off and burn all of the trees. Now that we have extremely dense forests due to fire suppression, the fires catch and become incredibly hot and they spread very, very rapidly. They just tend to burn through everything in the forest leading to this kind of moonscape fire scar situation that we see in some of these mega wildfires.

Mycelium is one of the only ecological ways other than fire to manage the excess biomass. Meaning that, if we’re not going to let the fire burn because the climate conditions are changing, and it’s incredibly risky to burn in forests, the safe operable burn window is getting shorter with each year due to changing climatic conditions, we need other ways to deal with the biomass. Using native microorganisms such as fungi which are evolutionarily adapted to being able to break down that material and turn it back into soil, is very advantageous.

In terms of what that looks like on the ground, when fire mitigation forest recruits go in and they remove a certain percentage of trees for fire mitigation purposes, instead of hauling that wood away, they can inoculate that wood with native fungi in order to complete that carbon cycle in a way that is more like what would naturally happen in the forest ecosystem by retaining that carbon onsite. Then simultaneously, the mycelium is able to accelerate the decomposition of that wood as well as hold more moisture within the wood, which helps to reduce the flammability while it’s decomposing. This holds more water within the watershed to make the whole watershed more drought resistant, and makes the whole landscape more drought resistant as well.

The often unintended consequence of some forest thinning projects is the subsequent dryness of the ground. When you take this dense canopy, and all of a sudden you open it up to a lot of sun, the vegetation there is more used to shade, and the microbiology is more used to shade. So when you just automatically make this super exposed ground, there can be this dryness factor. By creating this wood layer that’s inoculated with mycelium and giving it that living biological sponge, so to speak, we can mitigate the effects of excess dryness on the landscape.

Jonnah:

You are in the middle of a really big grant project. Can you talk about the grant, and who the partners are that are involved?

Zach:

This year, in 2024, we received the Boulder County Climate Innovation Fund, which is a fund made available by the Boulder County Sustainability Tax with the intention to support innovation in the climate change and carbon sequestration space. The reason that they funded our project is because they see it as an innovative, and scalable, and biologically sound way to deal with excess carbon in our waste stream, and help to sequester it back into the earth, instead of it burning or using fossil fuels to move it around.

We got support from the St. Vrain & Left Hand Water Conservancy District for that project. They decided to support the project because they’re very invested in forest health, conserving water resources within the watershed, and all of our work is taking place within the St. Vrain watershed. Those organizations were very instrumental in catalyzing this work, and we wouldn’t be able to do it without their support.

The Boulder Valley and Longmont Conservation Districts and The Watershed Center are the two field partners that we have. They helped us organize the relationships with the landowners and the sites where we’re doing the inoculation. Essentially they are overseeing the fire mitigation forestry piece of the project, as well as the landowner relationships. Then we are coming in and performing the inoculation work to help them reduce the amount of hauling and trucking of material that they might otherwise have to do as a part of their project.

To fulfill the goal of the project, what we want to be able to show is that by using these nature-based solutions in real life, field-scale, climate-change related problems, we have to demonstrate that we’re able to do it at scale in a way that is efficient and feasible. The scalability factor is a major component of that work, which is why we took on a larger scale project than we had in the past.

For us to get these methods into the hands of foresters that are doing thousands of acres of treatments per year, we need to demonstrate to them, as well as the communities that they serve, that these approaches are in fact possible and they can be done, and they have been done. The main goals are demonstrating that sustainability in forestry is scalable.

Jonnah:

Who are the farm partners in this, and how did you choose those farms? Were those pre-existing relationships that you had, or how did you choose who to work with?

Zach:

The farm partners are a part of the Healthy Soils Initiative that was also a grant that we received through Boulder County, and Zero Foodprint, as well as Wolfe’s Neck Center, which is operating through a USDA grant. Those projects are related but different in the fact that we still wanted to make use of forestry biomass, which is generally considered a waste product, but to incorporate that into a regenerative agriculture setting also using the same principles of the fungal inoculation as a way to transform woody biomass into a asset to the soil health.

A lot of our depleted agricultural soil in the world really is lacking two things. It’s lacking organic matter, and it’s lacking life. As soils move towards desertification, they have lower and lower organic matter profiles. They have lower and lower biological activity. Those two things together create an environment which cannot support much plant life, crop life, animal life. It also can’t hold much water or topsoil. Looking at that problem and asking, “Well, what do we have available to us in this area that could help us solve that?” The carbon biomass that’s generated out of the forestry projects is a huge source of organic matter that isn’t really being made use of super effectively in this region.

One of the reasons why is because it takes so long to break down. It’s not like hay, or compost, or chicken manure that’s automatically available, but there’s a huge quantity of it. If we can start to understand how to make use of that material and turn it into something which is valuable for farmers to use in a somewhat rapid way, then all of a sudden we have a huge quantity of this resource that wasn’t necessarily deemed that useful in the past. We partnered with seven different farms: Jack’s Solar Garden, Esoterra Farm, Yellow Barn Farm, Grama Grass & Livestock, Elk Run Farm, Ollin Farms, and Wild Child Farm.

We partnered with those farms because they are folks in the area that are involved in the original agriculture space that are open to new novel, innovative approaches to improving their soil health and soil biological activity. In partnering with them we brought biomass, fungal inoculants and slurries onto their farm, and incorporated them into their growing systems.

Jonnah:

You’ve been steeped in all of this science, and funding, and building your business. Are you still able to connect the philosophy or higher meaning of what drew you to this work initially around mushrooms? I’m sure the answer is yes, but how do you keep that alive in you as you’re in the thick of this rigorous detail that you’re in?

Zach:

That’s a super good question, and it’s not always the easiest thing to do. But that is the one and only thing that really motivates me to continue to do the work that I’m doing, and building out our team, building out our network, building out our relationships. Trying to adopt this work into our bank of methodology as human beings approaching potentially one of the most major extinction events on the planet Earth, and needing every tool in the toolbox that we can make use of, and listening to nature in order to address the situation that we found ourselves in. That kind of inspiration really is the only thing that motivates me to continue to do this work.

For me, I find a lot of solace in spending time in nature, taking a walk in the woods, in the mountains, and just looking, and just listening, and just paying attention. Asking for inspiration from the natural world, and having enough humility to try and just receive those messages as they come, and then translate that into our own work in the human dimension. Nature and all of our ecosystems that we live within have been operating of their own accord without a whole lot of human intervention for a very, very long time. Whether or not we’re taking notice of it, it’s happening. The more that we can pay attention and take a moment of gratitude, and a moment of just awareness around all of the complex systems that are happening all around us, under our feet, over our heads, between the trees, animals, birds, all of that stuff is happening all of the time, whether we realize it or not.

The more that we can tune into those processes, the more that we can start to readjust some of our practices that may be causing more harm than good. Also having a human community, and trying to emulate that kind of reciprocity between human beings is also super important. I think a major tenet of Boulder Mushroom is to be embedded in community and to be embedded in network. And that’s a teaching from the mycelium.

The mycelium is a network, a cellular network. It’s a decentralized brain, it’s a decentralized stomach, and a community is kind of like that as well. We are each an individual being, but we’re threaded into this much larger being, which is our community. That could be our neighborhood, our county, our state, or our world. I mean, we really, truly are connected in this great web. And I think that the more we can pay attention to that and pay attention to how we’re relating with other people, and both on a personal level and in a collaborative level, maybe the more that we’ll start to see these sort of rippling effects take place further and further out from our own little world that we tend to live in on a daily basis.