The Mad Agriculture Journal

Rx Return: Inside the Artist’s Process

Published on

May 06, 2024

Art and photos by

Max Sorenson

Interview by

Jonnah Perkins

A CONVERSATION WITH ARTIST AND CONSERVATIONIST, MAX SORENSON

Max Sorenson is a conceptual artist who uses his body to move across landscapes to capture unique patterns in nature. Mad Agriculture’s, Jonnah Perkins, sat down in conversation with Max from his New Mexico art studio to learn more about his process of using prairie burn char as an art medium for his collection, Rx Return, that is featured in the Mad Agriculture Journal Issue 11.

Jonnah:

I came across your work at the Overture Center for the Arts in Madison, Wisconsin, over the holidays and was struck by the eerie beauty of your sketches. I feel so honored to share your RxReturn collection in the Mad Agriculture Journal. For our readers, can you introduce yourself?

Max:

My name is Max Sorenson. I am an artist and conservationist currently working in Albuquerque, New Mexico. My work focuses on the intentional and careful expansion of our collective notions of human stewardship of the land. Recently, I developed work and spent time living at the Aldo Leopold Foundation in Baraboo, Wisconsin.

That experience allowed me to live and work on a single piece of land for a year and to consider all of that work and time spent out on the land with a perspective that was deeply influenced by the ideas of Aldo Leopold as well as some other contemporary conservationists working to do a lot of the same things that I’m interested in.

Jonnah:

What are some of your earliest memories as an artist of seeing patterns in nature?

Max:

A lot of my work focuses on the ways that I see humans interacting with the natural world and also on my own actions towards life outside of myself. Early in my life I was heavily influenced by my parents and the family that I grew up in. My dad works as a forester in Central Wisconsin and my mom is an avid gardener who grew up in a fairly remote farmhouse in the Driftless region of Wisconsin. So I have some really strong memories of spending time at that particular place at their farmhouse and the 80 acres that my grandparents took care of.

Some of those experiences that really have stayed with me are walking out to the mailbox to check the mail with some assortment of the almost 40 people that would gather there for Christmas or Thanksgiving or other family reunions. I also remember romping around outside with my cousins and building forts and exploring these two clumps of pine trees that we called the New and Old Pine Forests.

Those experiences with my family, who all shared, in their own way, a care for the land and an attention to it, have influenced the way that I both think about and actually act on the land and the things that I want to engage with. Though my own way of interacting with the land looks a little different from most of the people in my family, all of those experiences together brought me into a conversation with the land that started to view it as an extension of my already quite large family.

Jonnah:

I want to go back to two things that you mentioned. I’m curious about where in the Driftless your mom’s family’s place was, and then also, maybe this is part of the same question, but the New and Old Pine Forest, that is very interesting to me. Are those two different forests or is that one place called the New and the Old?

Max:

That’s a good question. My mom grew up outside of Galesville, Wisconsin, so pretty far western reaches of the Driftless, not too far from the Mississippi. The New and Old Pine Forests were separate clumps of trees, and they weren’t particularly large. I think forest might be a bit of a generous term for them. I’m actually not exactly sure of the origins of the new and old terminology. I think the old one was one where my mom and her siblings spent a lot of their time, and then the new one, for whatever reason, whether it’s actually newer in age, they didn’t spend as much time there.

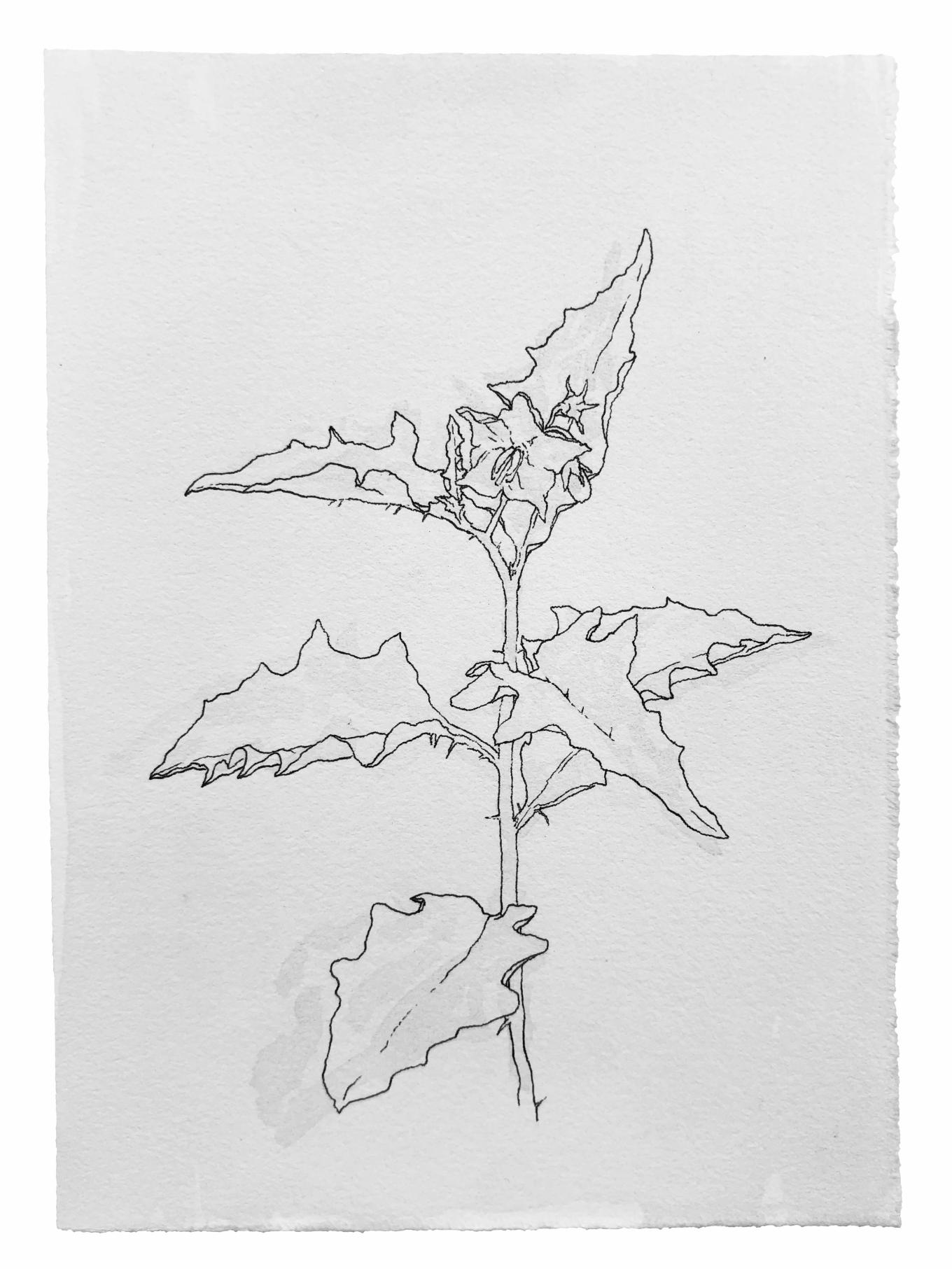

RxHorsenettle

Jonnah:

It’s just cool how kids name things. Your work is so original and I’m interested in talking about the process of conceptualizing a project. Is this something that happens over years or do you have flashes where it’s fully formed for you? What is that like?

Max:

All of my work is really rooted in time spent outside. The work that I treasure most and that I feel is most effective or impactful or meaningful, at least to me, is work that is directly rooted in some way in a practice of stewardship of the land. Especially while working at the Leopold Foundation, I discovered the connection that can exist between land stewardship work and my own more creative ways of expressing some of those feelings and things that I find important while doing stewardship work.

Basing the work within a physical and repetitive action, such as cutting brush or collecting seeds, is really helpful for me, personally, to notice patterns and to get a little bit away from the more heady and idea-laden confusing landscape of my own mind. The work that I make that is rooted in specific acts of land stewardship feels a lot more grounded and connected to the life outside of me, which is one of the main goals of the work that I’m trying to make—trying to connect with that life and to hopefully bring other people into that and to promote an ethic of care for that life and to promote slowness and attention when outside.

Jonnah:

For RxReturn, which is the piece that’s featured in the Journal, it’s almost like a performance art or a dance in that your body is physically part of the gathering of the art, which is really unique. In conceptualizing that project, how did you see yourself fitting into it as the performer of the creation of that work?

Max:

That’s a really good question. A lot of my work in the past has also involved different methodical acts, walking especially has been a really important part of a lot of the things that I’ve made in the past. So for this project, in that active return to the unit that me and the other burn crew members gathered to burn, that act served to honor that work, and I specifically tried to trace the path of the main head of the fire that we laid down on the landscape on that day. That attention to the way that the fire moved over the land, and then coming back to trace that with my own body and then to also have the knowledge that I was tracing the steps of a variety of other people that were there doing that work on that day, each of those different attentions to those actors on that specific unit, on that specific day, allows for both a celebration of that work and of each of the different cares and motivations that each person brought to that management act.

Also, I see this work as a ritualizing of ecological management, and, in a very personal way, a deepening of that work for myself in a way that helps me to continue to do that work, to see the importance of that work and to see the effect that it’s having on landscapes that today are so often damaged or less diverse than they have been in the past.

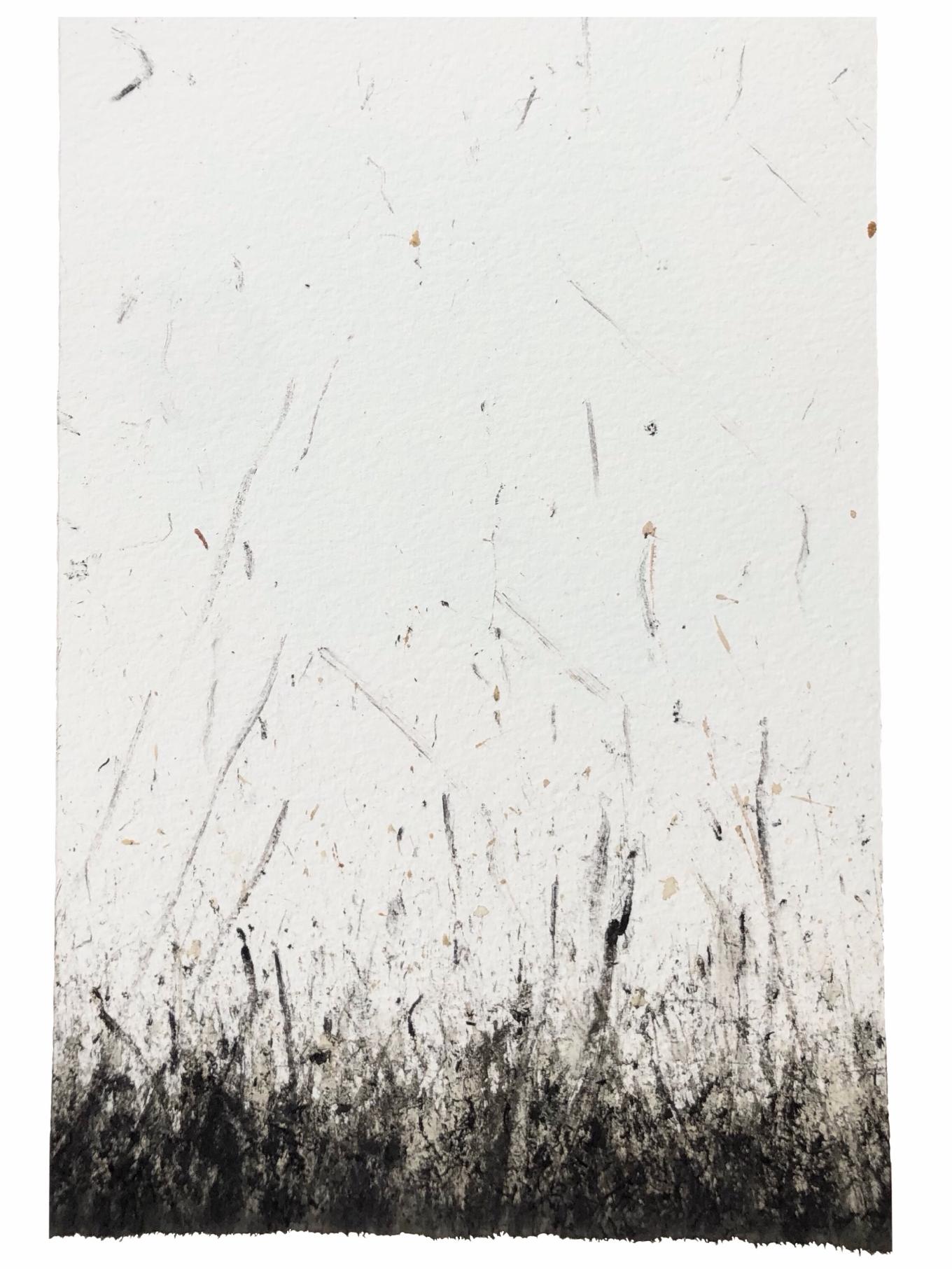

RxMap, Amy's Prairie

Jonnah:

What are some of the challenges that you’ve encountered as you’re working with natural mediums?

Max:

The challenges that come most often when I’m working with natural mediums and natural materials, and even just in a natural setting, come from a discomfort and a certain inability to sit with the loss of control and loss of immediacy that happens a lot in those settings and with that material that I’m collecting. Oftentimes, at the start, I don’t have much specific knowledge of how it will act or react to what I am doing to it.

Those are the main challenges and I think those challenges stem from a larger disconnection that almost all of us feel today and that are results of expanding convenience and comfort of life the way that we live it today, which, obviously, offers some incredible benefits, but also contributes to a distancing from the human and the more-than-human life that we share this land with and that we depend upon.

Jonnah:

Do you think that that discomfort in the chaos is an important ingredient in your work? Is that necessary and does it come through in the final expression or is it something that you’d go through privately?

Max:

That’s a good question and one that I don’t think I’ve thought of with respect to the way that that comes through in the work. I’m running through things that I’ve made in the past and trying to tap into that and see if that’s there. I think the challenges and discomfort might not always be physically or visually present in the final expressions but certainly in the way that I talk about them. That discomfort is there in all the work that I make that either celebrates the connection that I built while doing that work or while being outside and focusing on certain things. In that way, the celebration or honoring or joy in that connection reflects a healing of the disconnection and discomfort that I often feel, most often, at the start of projects.

Jonnah:

On the other side of that, what are some unexpected easy points in your work? And that could be anything from the weather cooperating or the wind blowing in the right direction to make your work easier to do.

Max:

Well, that’s the best part of this whole thing, I think. I really feel that I cherish those moments of unexpected wonder that serve to make me feel that connection to the land and all of the life that is around me and outside of myself. I’ll give an example of that with RxReturn, the project that’s being featured. This whole burn drawing project started when I was out collecting leaves and using a silly and methodical method of leaf collection that I’ve done in the past where I walk in a straight line, usually, but not always—sometimes I’ll be following a path or a trail. At every 10th step I bend down and pick up a leaf, and I’ve made some tracings from that act and from those leaves.

I was in the midst of doing that, looking at how that leaf size and shape would change as I went over a series of two or three ridges that are separated by lower areas of prairie. I was walking in a straight line, up and over those ridges and through those prairies, and collecting a leaf at every 50th step this time because it was a larger distance, but I was collecting those leaves in a brown paper bag.

This area had been burned a couple months previously in the fall, and at the end of my walk, I was just sitting down to take a break, and I noticed the outside of the bag that was facing forward as I walked was collecting the marks of the burned prairie and burned wooded units. That just felt like direct, physical evidence from the land that I was moving through it and engaging with it in a way that really fascinated me and made me want to dive deeper into that and to see how those marks changed under different ecological contexts, different geographical contexts, and different human contexts too.

RxWalk, Amy's Prairie

Jonnah:

It’s amazing that it just materialized through the act of walking.

Max:

Yeah, and I love that I’ve found a way to continue, basically, the same thing, just a little more refined with a piece of white paper rather than a brown paper bag.

Jonnah:

Do you have that original bag? Did you keep it?

Max:

I don’t think I do. I should have.

Jonnah:

When you set out on a project, do you have an intention of what emotions you want to create for your audience?

Max:

Yeah. A lot of my work, as I’ve said, focuses on promoting care for the land. Wrapped up in that, not really as an emotion but the emotions that are wrapped up in an ethic of care for the land are primarily, for me at least, are tenderness and slowness and intention, intentional attention that is paid to the landscape. As I continue my work and try to engage different communities of people and just move through the human world, I’m interested in seeing how people react to my work and to see if they’re getting those things from it.

My work, I feel, is very, very personal, and that’s hard sometimes for me. It feels almost selfish to be indulging these things that I feel I need to do when there are so many other ways that we can be working to heal and to change the way that we are currently living. I would like to see those things expanded, and I hope that, if not now, eventually, that I can at least help some people to find those connections, because I know I’ve had influences and artists that are working that have done that for me, and that have made me want to just spread an ethic of care for the land and to spend time slowly in it.

Jonnah:

It’s not uncommon for artists to feel like what they’re doing is not useful or a best use of time or resources. But I think art, like you said, will influence and inspire other people to want to be involved in the ecology of where they are. So I have felt that too, as a writer and photographer, it will create more interest in the land, which will ultimately be a net positive.

Max:

Yeah, that’s a good reminder, and I think I struggle a lot, too, with feeling the immense privilege in being able to do this work. There are so many people that, because of the systems that we currently live in, don’t have access to land, or have the time to develop a connection to it, and there are a whole slew of reasons that contribute to that. Often those communities are historically marginalized.

That’s been a hard thing for me to grapple with, is to feel okay doing this work. But I know, rationally, that the work is important and that through sharing my work I can try to serve in the collective effort to heal some of those things that are preventing people from connecting to the land.

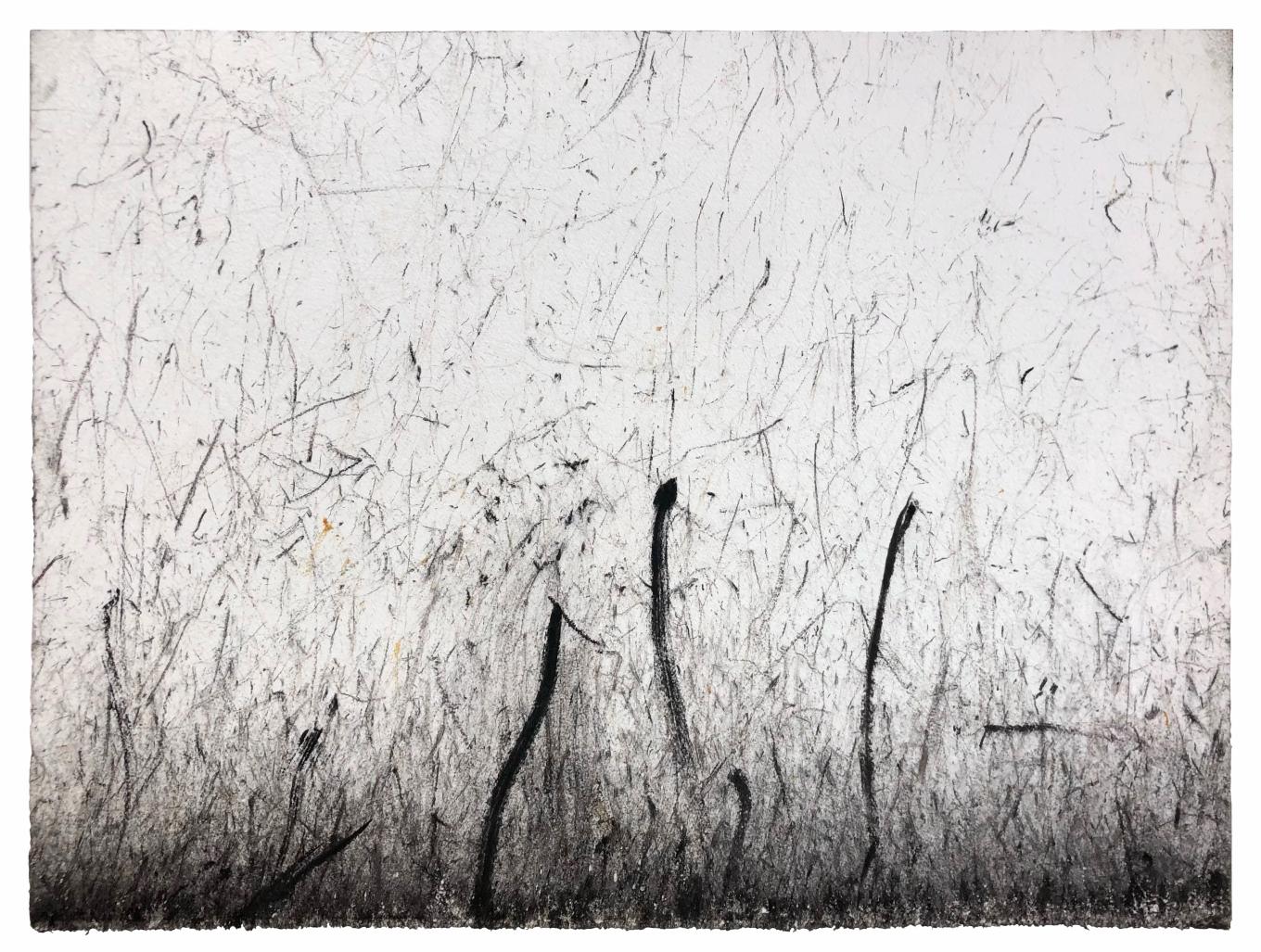

RxWalk, Kammerer Meadow

Jonnah:

RxReturn was done in Wisconsin, but you’ve recently moved to New Mexico. How are you encountering this totally new ecosystem and how is it influencing your work or what you plan on doing for your work for your next project?

Max:

The last six months that I’ve spent in this new place, I’ve felt a lot of discomfort, and it’s been quite difficult to continue some of the threads that I was working on and engaged with and passionate about while living in a fairly rural setting in Southwestern Wisconsin. I was working in the field and working directly with a piece of land and trying to steward it. It’s been difficult to find a similar sort of connection to the land here and its human communities too. It almost feels too early to describe how the ecosystem or all the different contexts of this place have started to shift my work.

I’m looking forward to finding ways to engage with the landscape in a more communal and a more practical fashion. I want to continue the RxReturn project in the American West. Here in New Mexico, I think the introduction of this project that walks through recently burned areas will add a lot of layers of complexity to the work in a way that I feel is really needed. That’s one thing that I loved and was really drawn to while working in the field and living on the same piece of land, is this endless stream of complexity that continues to unfold, and that it feels incredibly engaging to dive into.

Continuing this work in the West, there’s some really fertile ground for complicating both my understanding of our collective relationship to fire and for providing some space for others to hopefully sit with some of that complexity as well. It will draw from the highly destructive and devastating consequences of the increasing frequency of wildfires on this landscape and the grief that can be held both by people that live close to, or in those places, and also by the land when an incredibly intense fire rushes over it in a way that has not really been previously seen by that land.

Moving forward with this work and trying to really listen to both the people that live on the land and the land itself by picking up the materiality of those fires and by metaphorically picking up the experiences of the people that live with that ecological reality is really important work, especially as we go forward and climate change and previous fuel mismanagement contribute to fires that are increasing in severity and frequency.

Jonnah:

That’s so interesting to compare. In the Midwest, wildfire, it does exist, but it’s on such a different scale. We have such a different ecosystem, and these controlled burns that are happening on these rather small pieces of land are such a microcosm of what fire is. This next level for you feels like an exciting big jump. What are your thoughts on what your physical medium will be to transfer some of the carbon that’s created from the fire, or how do you plan to express this narrative?

Max:

I am excited about continuing the practice of walking through recently burned areas and continuing the very same process that made the RxWalk drawings and to see how the marks that are left on the page shift and how the overall average value of the page shifts. I am interested in marks made by larger burnt trees or a more intensely burned landscape, what that will look like on the page in comparison to prescribed fire in the Midwest and in comparison to the other drawings that I am able to make in the future.

I am also very interested in continuing to be open to other ways of collecting that material and other ways of honoring the realities of each fire that I interact with—both the positive and the negative—by using material from it, whether that’s continuing to make ink as I did in this project based in Wisconsin or directly using pieces of charcoal to draw, or recording audio or video. I am excited about how the new context that I introduce this work to might shift both the work involved in making it and the actual products that come from it.

Jonnah:

I’m really excited to follow along and watch it unfold on a bigger scale and bigger landscapes.

Max:

If I continue this work forward, I’ll learn so much from it and the main thing that I’m interested in learning is how to hold, create and honor the space that people need who are negatively impacted by some of these fires. Those stories are ones that we really need to hear and need to amplify to reckon with the realities of the effects that fire has in the West. I’m interested to see how those very same people can add a lot of complexity to this topic.

My work really centers around looking at how people are both successful and maybe not successful in inviting the sort of wild things that we are not yet comfortable with because of various systemic structures or tendencies that we have now developed in the way that we live on the landscape. It’s about diving into that and seeing how we can expand our communities of life even more to try to include all of it and not just the things that fit well into what we’ve decided our lives should look like on the land.