The Mad Agriculture Journal

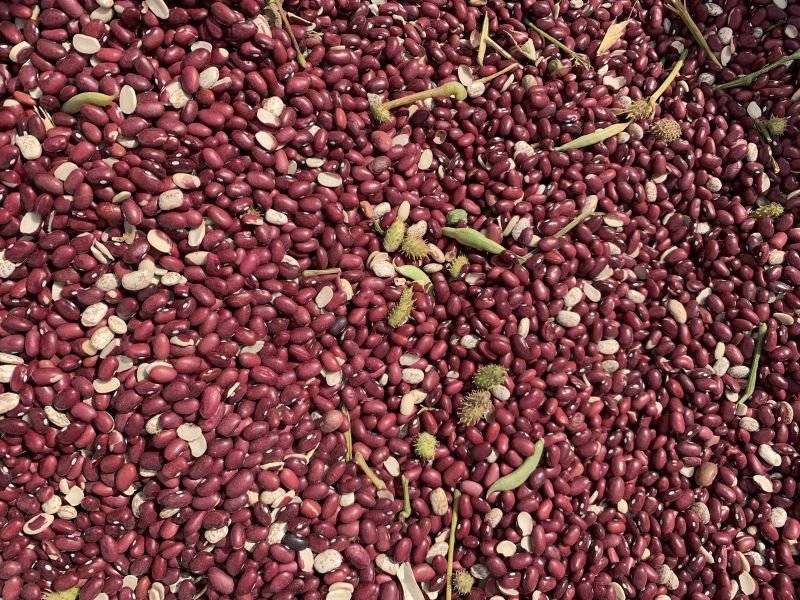

Boulder Beans

Published on

November 30, 2020

Written by

Tanner Starbard

Photos by

Tanner Starbard

Beans enable diversity. On the land, in our diets, and in the community and local economy.

Boulder Beans are good for the land and soil.

Throughout Colorado, very few farmers have a legume in rotation. If they do, it’s often alfalfa. Pulses for human food are lacking. Regional crop rotations would benefit from beans. A crop rotation benefits from diversity by reducing pest pressures and inviting a supportive growing environment to plant, manage, and harvest plants. The pests (including weeds, insects, and fungi) that inflict pressure on the growing of one crop or plant are not always the same for another. A winter wheat rises early in the year, competing with and reducing the abundance of other undesirable cool and early plants, then after a midsummer harvest, the land opens up for later and warmer plants to take over. Corn, sorghum, or beans are planted and harvested later, creating a different window of opportunity that allows cool and early plants to thrive. Pests and fungi that feed upon certain crops and seeds aren’t as keen on other roots and plants so their populations dwindle in the between times without their preferred food (and abound when their favorite crop is grown year over year). Some plants like rye or buckwheat are commonly grown as cover crops because of their allelopathy—the active reduction of undesirable plants through chemicals they exude through their roots. This concept of breaking weed, insect, and fungal cycles with strategic management of plants and their life cycles is often referred to as Integrated Pest Management; a diverse crop rotation is the central pillar to this approach to cultivation that reduces the need for chemical pesticides like glyphosate and neonicotinoids and mechanical disturbances like plowing and tillage.

The benefits of beans go well beyond rotation and diversity. They help bring nitrogen into the ecosystem. Nitrogen is the most abundant element in the air but is scarcely available in a ‘plant-available’ form in the soil; we know that plants utilize atmospheric carbon, so why don’t they just grab the nitrogen they need through photosynthesis also? Elements bond to one another through their electrons as if holding hands. Remember the game red rover in elementary school where you break through the line of classmates holding hands? Imagine if that line was three people deep instead of just one or two… much harder to break! Atmospheric nitrogen is triple bonded so it takes a whole lot of energy to break those atoms apart into a form that plants can use and later turn into amino acids and proteins (plants need a balanced diet, too!). There are two natural ways that atmospheric nitrogen becomes plant-available: lightning strikes and biological ‘N-fixation’, where special types of soil bacteria have the ability to convert atmospheric N into plant-available forms, like ammonium. Humans discovered biological nitrogen fixation in 1901.

About four years later, Fritz Haber developed the industrial process which turns atmospheric N2 into plant ready NH3 ammonia that is commonly used for plant fertilizer. The process has enabled incredible gains in productivity but requires a ton of energy to accomplish - it takes a lot of fossil fuel to break a triple covalent bond. And, the product is highly volatile (see the recent port explosion in Beirut as an example). The story of fertilizer is one of war and food, which I’ll save for later.

Leguminous plants (like beans!, peas, peanuts, clover, and alfalfa) engage in a mutualistic relationship with prokaryotes that break airborne nitrogen gas into a form that plants can use in exchange for energy, produced with sunlight. These bacteria often reside in little nodules on the roots of leguminous plants (dig one up and look!). These nodules create microenvironments that are free of oxygen, where the prokaryotes use the oxygen-sensitive enzyme, nitrogenase, to convert N2 to ammonia NH3. These nodules harken back to the Proterozoic Earth when cyanobacteria, which can photosynthesize (remember oxygen is a byproduct of photosynthesis), limited the accumulation of atmospheric oxygen in favor of N fixation. Then, land plants evolved and decoupled photosynthesis from N fixation, creating the Great Oxidation Event, about 2.4 billion years ago. So, next time you go looking for nodules, remember that they are an adaptation to a changing world to host relic creatures of an ancient time.

The benefit of legumes to agricultural ecosystems extends beyond the direct addition of plant-available nitrogen. Plants transform atmospheric carbon (CO2) and water (H2O) into carbohydrates and sugars, like glomalin. Plants use these energy-rich carbon compounds to fuel the economy of soil. The main area for market transaction is the rhizosphere, the interface between plant roots and the soil community. Imagine a subterranean silk road bustling beneath your feet. The rhizosphere is perhaps the most biodiverse place on the planet from a species-to-area perspective, and there is much more than carbon and nitrogen in exchange.

Plants and soil biota are swapping whole packages of elements including micronutrients like calcium, magnesium, and iron that plants and humans need for healthy functioning. Critical elements for growth and metabolism don’t move in isolation; they are tied to carbon-based molecules. The addition of artificial fertilizer short-circuits the soil economy. There is growing evidence that fertilizer reduces the incentive of roots to grow, expand and engage in the subterranean marketplace. When plants get nitrogen for “free” from synthetic fertilizers, they can grow quickly and maximize grain yield, as they are disincentivized from ‘feeding’ the soil economy as soil carbon dollars are invested above ground, and not below.

There are downstream consequences. First, the soil community is less vibrant and less active because plants dial back root growth, i.e. the subterranean carbon pump that feeds soil life. Second, there are impacts on crop quality, resilience and nutrient density. If plants reduce their root growth, then they also reduce the update of micronutrients piggybacking on the trade. In turn, we also miss out on these important micronutrients. Plants can still grow, but they are weaker and less nutrient dense. This idea is debated, vigorously. But, sometimes data is required to see the obvious.

Look at society and our food system. We are malnourished. Carrots and beans aren’t what they used to be. They are less nutrient dense. Instead of getting our nutrients from carrots and beans, we end up adding them into our diet through vitamins and supplements, much like farmers today often add these micronutrients to the soil as amendments from outside the system. Like nitrogen in the air, these micronutrients abound in the soil. Plants can’t find them out of thin air, but rather invest in the soil economy to find a return. In the chemical-industrial agricultural system, the underground economy is anemic and uninspired. Fertilizer truncates an ancient relationship between plants and soil, with devastating consequences. Which brings us back to how beans bring diversity and health to the land…

A balanced and diverse crop rotation uses ecological knowledge, time and space to create a setting where each unique plant variety can thrive. A crop rotation also brings certain structural and chemical characteristics into the soil so that all the life below ground can thrive also. Beans are part of a crop rotation that makes sense for the Colorado agroecosystem, and makes sense as part of a balanced diet that makes sense as Colorado cuisine.

Beans, beans, the magical fruit.

The more eat, the more you toot.

The more you toot, the better you feel.

Let’s eat beans with every meal!

Plant based proteins are a good thing. They have fiber and are loaded with proteins that are complementary to meat. Beans don’t need to replace meat entirely, but there are a bunch of reasons why beans and other plant-based proteins deserve a routine seat at everyone’s table, and often. Society is awash in nutrition science, dietary strategies, and food fads of every sort. Beans are a piece of the simplest wisdom, as Michael Pollan says, “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.”

Plant based proteins are often touted for their resource efficiency (less water usage, smaller carbon footprint, less water pollution) compared to animal proteins, but those comparisons do not always capture the full story; comparing local and pasture-raised beef with soybeans grown in a deforested Brazilian field makes for a drastically different comparison. Boulder Beans are a direct alternative to industrial protein production: The acres of land upon which Boulder Beans are grown typically produce feed for dairy and beef production in Weld County. The calculus is clear: eating Boulder Beans in Colorado requires fewer resources than the alternative animal protein feedstock that would have otherwise been raised on the same land.

The industrial food system has become the norm in many places, and with the decline of soil health we also find a decline in human health. As we do to one, we do ourselves. We need to re-discover and reimagine how to nourish our bodies, which begins with nourishing the land.

More often than not, we do not know where and how our food was grown. Not only does this compound our separation from the places and people we depend on, but it also reduces our ability to support the methods of agriculture that align with our values and health. With Boulder Beans, we are trying to stitch together new supply sheds that create and maintain ecological and human health at the same time.

For example, most dry beans are sprayed with glyphosate (i.e. desiccated) close to harvest to help ensure uniform maturity and improve the efficacy of harvest. Boulder Beans are always non-dessicated. We are working hard to communicate this benefit to buyers and consumers, creating safe and nutritious food from soil to mouth. Boulder Beans grow healthy communities, healthy people, and healthy places.

The heritage of agriculture in the Front Range is more than a memory, it remains an important pillar of the local community and economy today and into the future. Boulder County’s agriculture lands have been managed for decades, often intergenerationally, to grow a mix of food for people and feed for animals. As regional food processing, storage, and distribution infrastructure has been pushed away and the high demand for feedstock from nearby animal production facilities has continued to grow, the proportion of human food to animal feed has skewed in favor of feed. Even many of the food crops that are grown at midscale farms enter into the domestic and international food web, sparsely to be eaten within the area. Farmers and citizens alike want to restore a balanced crop rotation that favors the growing of food for the region. Boulder Beans encourage sound stewardship and healthy food to be grown for the local and regional community.

For a farmer to grow food for the community, there must be a way to get the crop to market. Whereas there used to be at least five local aggregator-distributor enterprises in the northern Front Range just decades ago, the options for a farmer, like Jules, have dwindled and the competition that elicited an attractive suite of prices and practices has dried up. A farmer growing midscale (200-2000 acres in operation) beans is currently stuck selling into the commodity system at prices too low to justify growing them in their rotation. In this system, farmers can expect to receive .20-.25 cents per pound of beans (usually sold as $20-$25 per hundredweight), while bean eaters pay closer to $2.00 per pound at retail outlets like King Soopers. As farmers gain access to the local market, they can earn a higher share of the food dollar without raising prices for the community. Improved revenues for a bean crop encourages and allows farmers to diversify their rotation and feed the community and region in which they live!

A clear and committed demand for beans provides the basis for the investment into and redevelopment of regional food systems by demonstrating a reliable market that will pay back the investments over time. Working backward to the field from a bite of beans looks like this:

Before you ate the beans, they had to be prepared (soaked and cooked, with some seasoning)

Before the beans were cooked, they were bought from a wholesaler or retailer

Before the beans were bought, they were stored (typically in bags ranging from 1 - 50 pounds)

Before the beans were stored, they were cleaned and bagged (ideally in a nearby facility)

Before the beans were processed, they were harvested (ideally with specialty equipment)

Before the beans were harvested they were grown (in a diverse rotation, with fewer chemicals)

Before the beans were grown, the farmer made a plan (a farmer can only grow what will sell).

Each of those steps in the journey from fork back to farm relies upon all of the other steps to be viable. Beans (like wheat and other staple crops) are grown here and are eaten here, but because many of the other steps occur elsewhere and in a commodity system, there’s no way to know if the food we eat actually came from the place we live. Currently, a different person or business is responsible for every step in this journey, which spreads the food dollar into more hands, with barely any making it back to the farmer. Several crops like wheat and beans can share the infrastructure that enables the harvest to kitchen phases of the journey. Luckily, every step has and can happen in the Front Range, we just have to re awaken the pieces!

Local and regional procurement enables local and regional processing and both of those encourage local agriculture to grow the crop. All of these actions occur right here in our local economy! This is why products with the Colorado Proud label can be such an important indicator for using your dollars at the store to create the world and community you want to live in.

Staple crops like beans and wheat create resilience through easy storage, minimal processing, easy preparation, and cultural relevance for diverse communities in the region. Disruptions to commodity supply chains and meat processing plants can cause increased food security, as was witnessed with COVID-19. Beans provide stable, affordable and reliable protein for nearly any diet and require less energy-intensive infrastructure throughout the farm to fork journey. From food pantries to institutions like schools and hospitals to restaurants and retail, Boulder Beans bring value and nutrition to the entire Front Range community.

On the farm, diversity in crops and markets brings resilience and flexibility to the enterprise. In recent years, higher and higher shares of farm revenues will come in the form of direct government subsidies like Revenue Protection. While some of this year’s support is due to the economy-wide effects of COVID-19, a high baseline of subsidy already exists in agriculture and the need for greater payments demonstrates the lack of resilience in a system composed of complex domestic and international supply webs and markets. Regional food systems for staple crops like beans provide farmers like Jules Van Thuyne the stability to survive through down years and the opportunity to thrive by growing the food that the region wants and needs. Clear demand and market connection for beans will allow farmers like Jules to purchase specialty harvest equipment that leaves fewer beans in the field, reducing food waste and improving farm-level economics. Let’s eat!