The Mad Agriculture Journal

Carry the Water

Published on

March 24, 2025

Written and photographed by

Joe Grant

On the first day of summer, I wake up before sunrise, prepare coffee, and walk the dogs on the circuitous half-mile trail around our yard. We walk slowly, taking in the sights and smells, observing subtle changes along the path: fresh bear scat, turkey prints in the mud, a ground squirrel burrow, and endless new sprouts of Gambel oak. A few wild iris still bloom in the meadow though most are split, dry pods ceding ground to Russian knapweed and Canada thistle.

The past week had been a scorcher in southwest Colorado, intensifying the late-spring snowmelt in the high country. I had been closely monitoring conditions as I prepared to leave on a 12 day hike around the San Juan mountains. Most of the terrain I would be traveling sat well above ten thousand feet and too much snow up high would be physically taxing and potentially treacherous. Of far greater concern though was the impacts of rapid snowmelt depleting the watershed, and setting the tone for yet another daunting wildfire season.

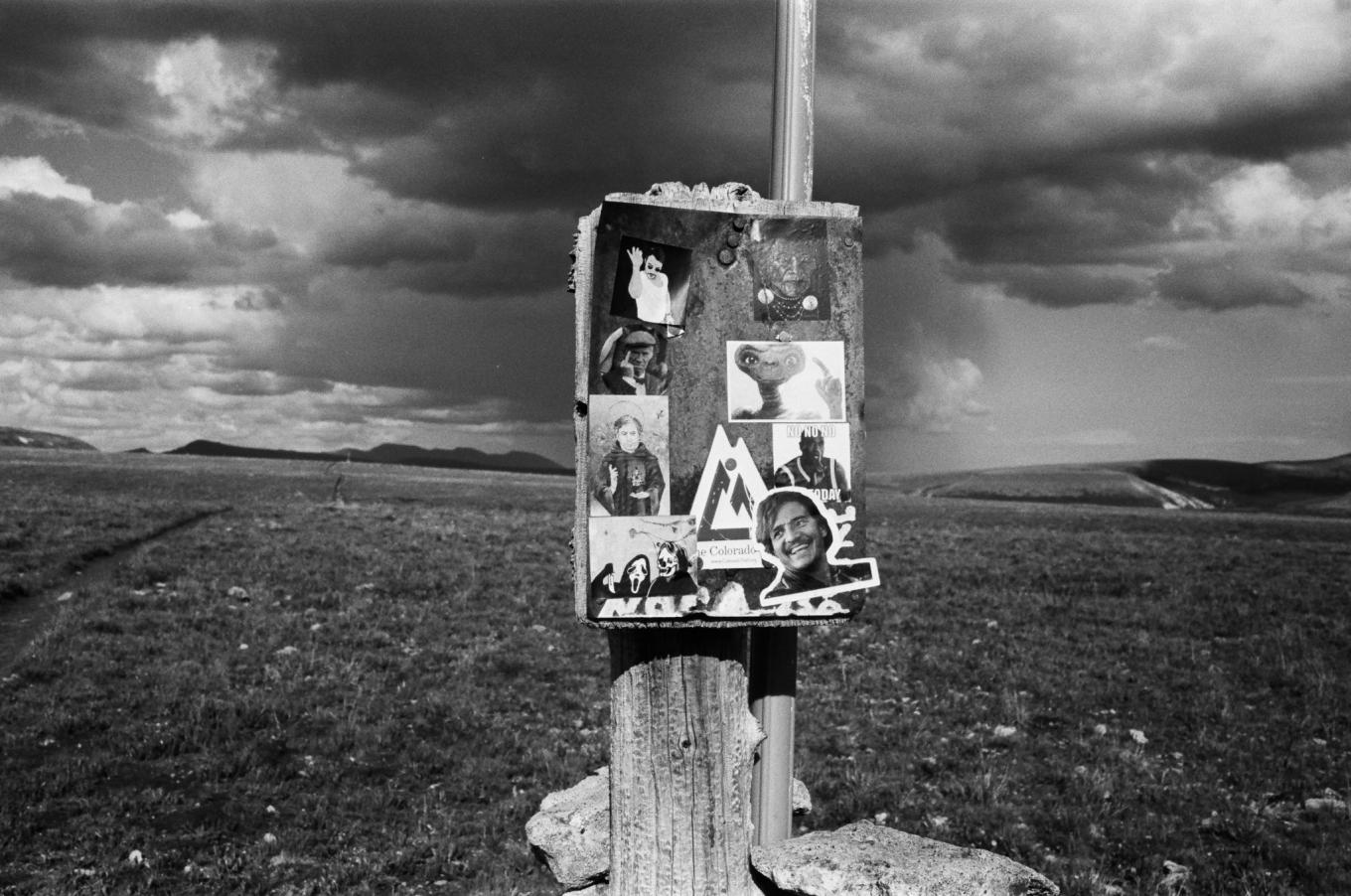

As I sip my second cup of coffee, my worries about fires are muted by the sweet sound of rain drumming on the shed’s metal roof. I grab a thicker raincoat, shoulder my pack, and set off north to the Weminuche Wilderness. This wilderness area is the largest in Colorado, spanning close to a half-million acres, yet it encompasses only a fraction of ancestral Nuche territory. Despite settlers’ formidable efforts to tame this place by way of trains and dynamite, its wild character persists and commands respect and humility.

The heart of the wilderness is only accessible on foot and is roughly a day’s walk from home. The foothills stretch to an elongated ridgeline that cuts through dense forest of aspen and ponderosa pine. Fog envelops burnt and fallen timber strewn across the hillside exuding a certain eeriness – a feeling heightened by the intermittent explosion of grouse into sight. As I gain the high mesa, a herd of elk moves swiftly through the trees, bugling. Below us, the white tent of a hunter’s camp and sheep stand out in the green pasture. The high mountains ahead live in the imaginary space as dark clouds close in around me.

First comes the rain, then the hail. With nowhere to hide, I seek refuge under a bush. I sit next to a pile of small animal bones, tuck my pack between my legs, pull my foam sleeping pad over my head, exposing my bare hands to the beating. I close my eyes, and take deep, slow breaths. Thunder rumbles. I count. One, two, flash of the spirit!

I count. I breathe. I wait. The storm rages on, then just as suddenly as it came, it is gone. The warmth of the sun on my skin brings me to tears. This is what I am here for: to feel it all, to nurture and be nurtured.

I sleep in the dirt under the full Strawberry Moon and visit the god of the winds. I climb mountains and kick steps down steep snow-filled gullies that run off into swollen creeks. I cross beaver dams, follow faint paths through thick willows and greet bull moose. I watch the porcupine breathing like a prickly bellow stoking the fire within. I listen to the coyote howl. I follow the Continental Divide to the great pyramid, zigzagging off its summit along elk trails to the headwaters of the Rio Grande.

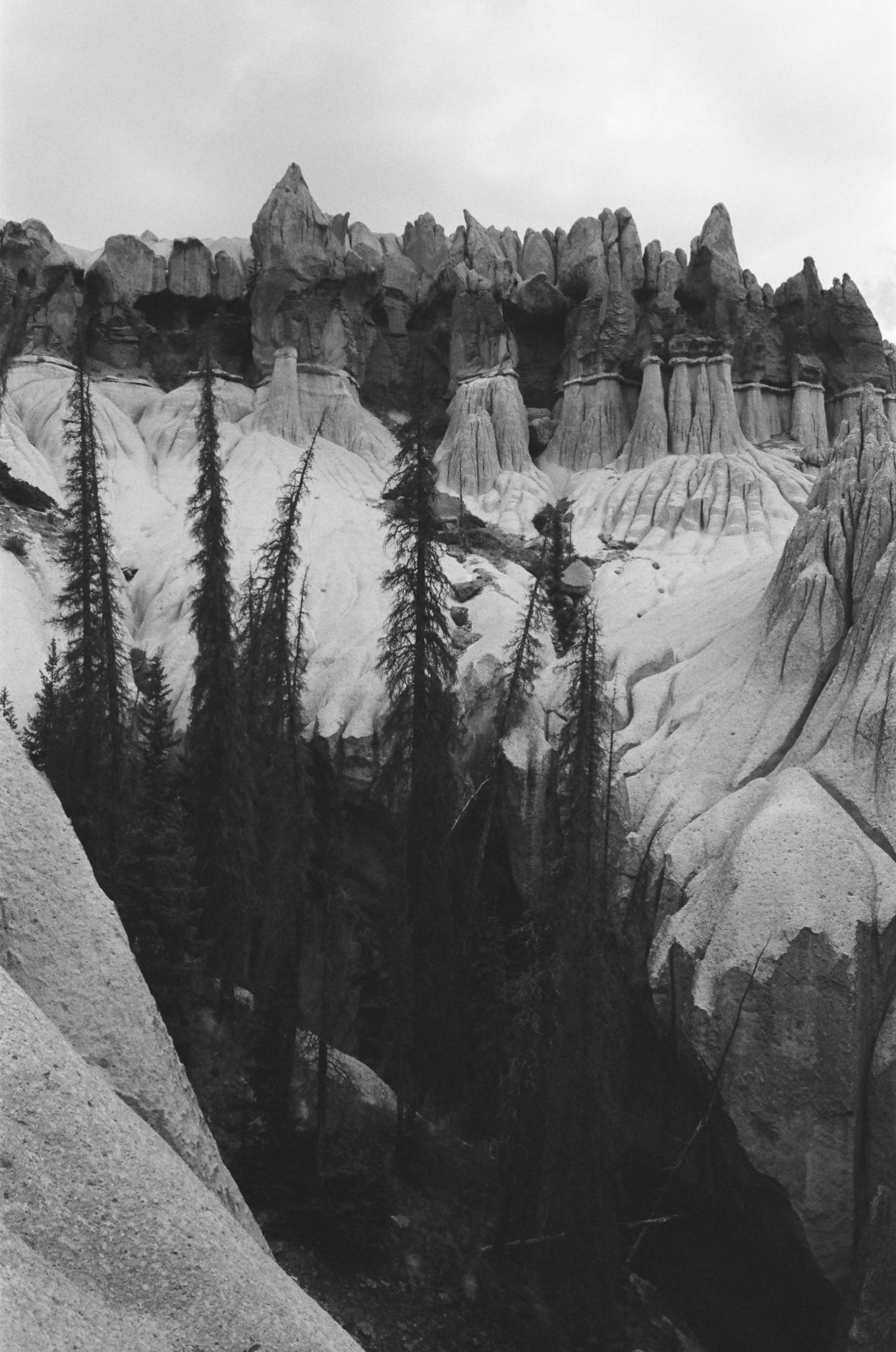

I walk to the far eastern reaches of the San Juan mountain range to the La Garita Caldera, site of one of the largest volcanic eruptions in history. Here, the wide open plains are dotted with cairns resembling stupas that lead deep into the hills to reveal vestiges of the original fire. Tall spires of ash stand in formation like a mushroom patch. A trail of fresh grass weaves through a forest of Beetle Killed Pine circling the hearth. I amble, spellbound, the minutiae of sensation bringing me back home.

One morning after my return, I was out with the dogs on our usual yard loop, when we happened upon a mountain lion kill. Alerted by the stench of rotting flesh and a swarm of flies picking at the carcass, my first instinct was to pull the dogs closer and look around, fearing that the cat might not have finished its lunch. But, it was long gone and over the next few days, foxes, crows, and vultures wiped the bones clean. Then the mycelium took over, feeding the soil, connecting all things, life living afterlife. The wild is not an abstract relic to be visited on occasion, it’s in the water, it’s where we live.