The Mad Agriculture Journal

For the Love of Plants

Published on

January 29, 2025

Written by

Emily Rose Haga

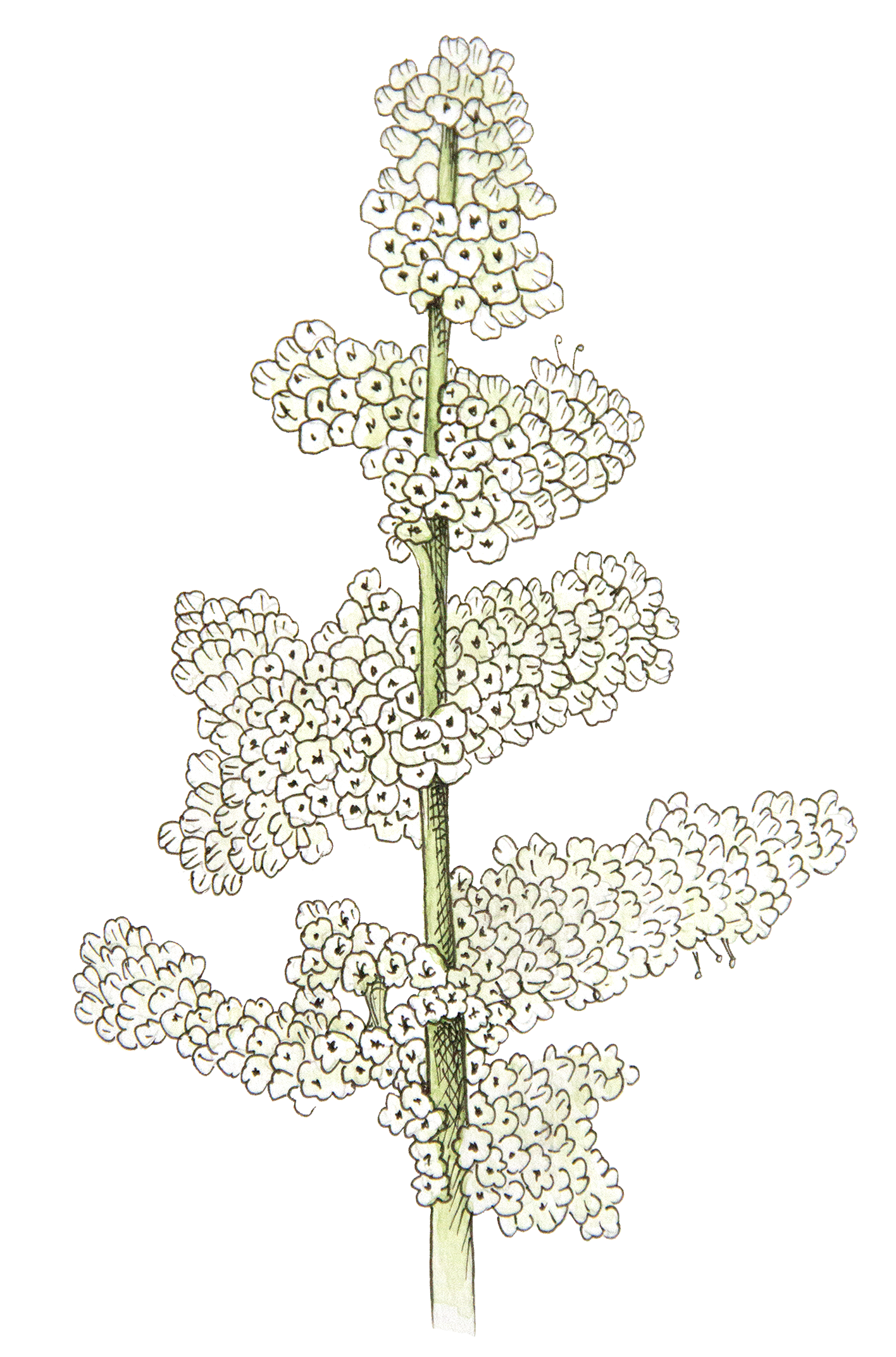

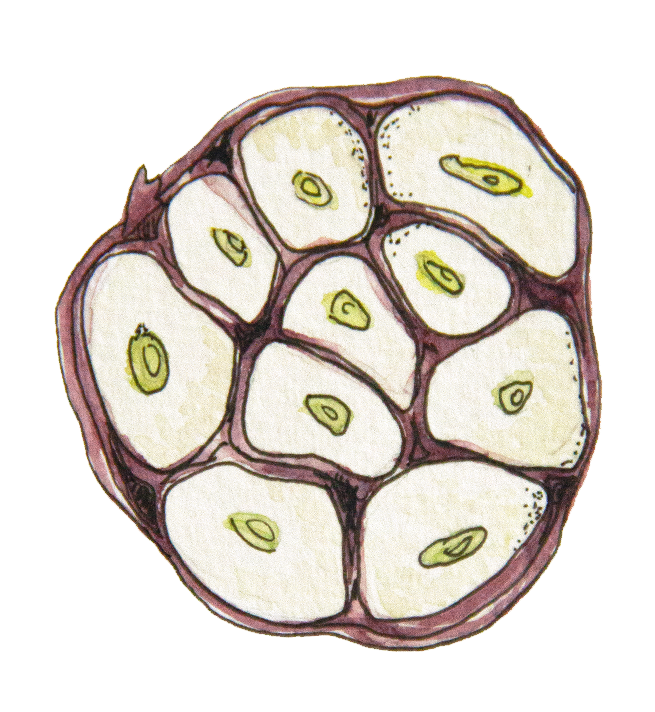

Illustrations by Catie Michel

Photos by Jonnah Perkins

Humans are so lost

making war

while robins make their nests

Why do we resist our nature?

When we are our best selves

in the garden

in the kitchen

on the land

In a world where humans are increasingly disconnected from nature, our relationship with plants and the land that sustains us feels more fragile than ever. Humanity faces immense social, political, and environmental challenges, and many people are feeling a strong call to action in their lives. As someone who has spent the last 25 years immersing myself in the world of seed conservation and plant breeding alongside others who believe that preserving biodiversity is key to a more sustainable future, I believe one of our most important sources of hope is in the quiet resilience of seeds and the stories they carry.

With 2024 being the 100-year anniversary of Nikolai Vavilov’s groundbreaking theory on centers of crop origin, I can’t help but wonder: what would he think of the state of agriculture today? Have we honored his legacy, or have we strayed too far from the symbiotic relationship between people, plants, and the land? The answers may lie in the seeds we’ve saved—and the relationships we’ve lost along the way.

Since Vavilov published his ideas about where to find the greatest diversity of wild ancestors and close relatives of different food crops, they quickly became foundational to modern plant breeding world-wide even though tragically he would later be starved for his scientific beliefs. Efforts around the globe have focused on building and maintaining seed and plant collections to preserve crop diversity before it disappears from places where it originated. Today these are primarily managed as a resource for the world’s scientists and plant breeders to study and use for crop improvement.

When thinking about his legacy a century later, I try to imagine how it might have changed our relationship to food and agriculture today had Vavilov reframed his theory as “centers of coevolution” instead of centers of origin—or even “centers of diversity” later used by American agronomist Jack Harlan. If preserving the human relationships with the plants and land was regarded as equally important to preserving the crop diversity, would we see the definition of these centers expand to include the culture as well as the geography? Instead of looking to crop diversity extractively as a disappearing reservoir of useful traits to be rescued by skilled scientists trained to preserve the world’s resources, would it be also regarded as a renewable resource that can still be generated by anyone, anywhere?

The growing loss of relationship between plants, people, and land at the everyday level of human existence threatens not only the diversity from primary centers of origin where crops were first domesticated, and the secondary centers of diversity where further adaptation and diversification historically took place but also unknown iterations of what that could look like still to come. Putting all our faith into businesses, governmental institutions, and nonprofit organizations, to take over the responsibility of preserving our collective heritage—which are understandably limited by their own constraints and sometimes short-sightedness—puts the future of crop diversity at risk just as much as the existential threats we face like war and climate change.

The Seed Trade Census completed every five years by the nonprofit Seed Savers Exchange to assess changes in the availability of open-pollinated varieties to gardeners and small-to-medium size farmers does offer some glimmers of hope that regional seed systems and foodways have recently been strengthening in the U.S.—at least at the commercial level. Their last survey from 2020 found a significant increase in the biodiversity of several crops when compared to earlier editions of their census, as well as an earlier 1903 publication by the USDA on American vegetable varieties. This was measured in terms of the number of varieties available for major crops (like beans, lettuce, tomato, pepper, and squash), as well as minor crops (like sweet potato, garlic, soybean, eggplant, quinoa, and chicory-radicchio). Some of these crops transitioned from minor to mainstream in that time.

In addition, they measured significant growth in the number of independent seed companies that offer seed in different regions. This trend marks a promising shift in the landscape compared to an extended period of consolidation and extinction of small and medium seed companies in the 20th century—coinciding with a renaissance of local food and organic farming movements in America that began in the 1990’s and continues today.

Despite this promising overall reversal of these trends, their research also showed that more than half of the varieties available today are only offered by one source. In fact, only 14% of varieties are commonly available from more than five sources—which puts the other 86% at considerable risk of disappearing from the seed trade entirely, particularly given the historical levels of both variety and seed company turnover. One interesting example that helps further highlight the fragility in the seed industry was the “Pepper Gate” scandal of 2023—where a seed mix-up by just one company who supplied to a chain of others led to thousands of home gardeners unintentionally growing banana peppers instead of jalapenos across the U.S.

Moreover, their latest census research also showed that the availability of commercial varieties in many crop types continues to be in “profound decline”—including beets, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, carrot, cauliflower, celeriac, celery, onion, radish, spinach and turnip. Notably, many of these are traditional storage crops that have historically played a vital role in winter survival for certain cultures. However, their biology as biennials is more complex than that of many other crops, as they require two growing seasons for seed production–forming bulbs in the first season and flowering in the second.

Today’s researchers and breeders who are using the crop diversity collected by gene banks largely use it to develop varieties that will perform in production systems that are increasingly mechanized, optimized, and controlled through things like fertilizer and chemical inputs or climate management. They also work in parameters that are driven by strong financial, logistical, and market factors. However, it’s also important to reflect on what we may be leaving behind when the collective work of previous generations is no longer carried out by so many hands and hearts across the wide swath of bioregions and microclimates on earth. There is an abundance of regional and cultural needs and opportunities that unfortunately just aren’t served by these models today.

I once had a professor, who taught the history of world vegetable crops, challenge the class to imagine what kinds of new crops we might domesticate today that weren’t already. I loved this question—ever since imagining how edible wild plants that humans frequently forage could metamorphosize into new forms with a little time and attention, or how existing crops could be further diversified by ongoing coevolution between plants and people.

One of the most fascinating real-world examples we have to look at for inspiration is in Brassica crops, which were independently selected for different plant parts (i.e. roots, leaves, stems, flowers, flower buds) by different cultures in different regions of the world. By selecting from a wild green within the edible species Brassica oleracea that grew across the Mediterranean and northern Europe for example, we came to have vegetables like kale, collards, broccoli, cauliflower, kohlrabi, cabbage, and Brussels sprouts. In a closely related species called Brassica rapa, different cultures across Asia created vegetables like napa cabbage, mizuna, bok choy, tatsoi, and turnips.

Another interesting historical example is the secondary diversification of apples following the movement of peoples and apple seeds from one continent to another during the time of European diasporas to the Americas. Because of the government’s incentive at the time to grow apple trees on land as a way to establish land rights, a tremendous amount of apple seeds were planted during a rapid wave of expansion of new people occupying these lands. The remnant trees and orchards that remain represent a unique set of apple diversity when compared to the apples growing in the continents of Asia and Europe—including characteristics that are useful for fresh eating, storage, baking, canning, and cider.

Within the seed industry framework of plant breeding, the ability to pursue opportunities for crop improvement within market classes that are outside of the “standard” categories (let alone explore all new ones) is rather limited due to very real business constraints—even within the most creative and innovative companies. Although varieties with unique or novel colors, sizes, shapes are more widely available than ever before, these are far less focused on unless there is an incentive to do so. Because of this fact, not only does maintenance of older open-pollinated and heirloom varieties commonly suffer within the industry, but whole crops or market categories are sometimes abandoned or just never really given a chance to reach their potential.

With the massive shift in traits being focused on by business entities in comparison to the generations of people who previously selected them, what are we missing out on that could be important to our future survival as a species? Will these choices we’ve made in recent history come back to hurt us later?

We can look towards university plant breeding programs with some hope to be able to explore agricultural opportunities that fall outside of the typical seed business model. Yet these programs too are competing for limited funds, and support for projects outside of the commodity or mainstream crops is extremely limited – not to mention that much of this work ultimately feeds back into the same industry pipeline. The very ground on which the research farms carry out their work is also increasingly at risk of being on the chopping block as leadership changes happen and college budgets get cut or future revenue-generating opportunities considered.

While there are careful preservation strategies in place at gene banks like Seed Savers Exchange, the U.S. National Plant Germplasm System, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, and others throughout the world who care for the already existing diversity that has been collected – none of these are impervious to the same challenges and risks as the industry and academia are. The seed collections held by gene banks in Ukraine, Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq have been damaged or destroyed in recent periods of war, while a collection in the Philippines was affected by both a flood and a fire. The institute Vavilov started himself nearly faced ruin—not once but twice—due to war and economic factors in Russia over the last century. Svalbard too—which is designed to be the world’s back-up seed vault, representing 13,000 years of agricultural history buried in a mountain in the arctic circle for safe-keeping—has even once been affected by permafrost melts as the world’s weather patterns change. This has led to some recent consideration of even putting a gene bank on the moon as conditions on this planet become more unpredictable.

Unfortunately even the strongest public entities here on earth (or perhaps elsewhere one day) can suffer from lack of critical funding, climate change, war, and other very real existential threats—the same things faced by Vavilov and his colleagues 100 years ago—and more. While the crops in the care of these places are stored in state-of-the-art ways intended for these living libraries to last a very long time, the schedules for regeneration of the varieties (i.e. growing them out and making new seed) can also sometimes be on the scale of decades or longer due to insufficient resources to do so more frequently. I can’t help but wonder – is this timeframe sufficient for evolution and adaptation to occur, given the world around us is changing at such a rapid pace?

During Vavilov’s lifetime there were massive debates about how traits were acquired and passed down, as the understanding of DNA being the basis of inheritance was not yet known. Vavilov was a proponent of Mendelian genetics and believed that it could be practically applied by finding an existing trait of interest and selectively breeding it into new varieties over several generations. This was the basis of his quest scouring different parts of the world for biodiversity that humans and nature had adapted to specific conditions where unique traits might be found to work with.

Today we know that in addition to the Mendelian inheritance of genes through chromosomes of DNA, environmental factors can indeed cause changes in the expression of DNA (by turning genes on/off or dialing them up or down versus changing of a gene’s DNA sequence itself), which are also passed down through generations in a heritable way—a phenomenon known as epigenetics. The applications of epigenetics in plant breeding in comparison to traditional genetics is yet to be seen. Research in plants is beginning to reveal how plant genes are influenced by the ecosystems around them – including relationships with soil microbes and different growing environments (like organic vs. conventional). In humans, much of our current understanding about epigenetics relates to heritable changes in gene expression as a consequence of exposure to harmful things like chemicals, plastics, and stress.

Though the work of the collective is far too big in scope and importance to be taken on by just institutions or businesses alone – it’s important to realize that it’s also far too big for any one individual or community to take on alone either. It’s common to want to jump into big and bold actions to help save the day given the weight of this collective existential crisis we face. However, the fallacy of the hero is something that can easily trick people into taking on too much or expecting too much of others. Sometimes even the most well-intended and well-meaning efforts can create a lot of harm when people lean too much into the savior mindset of activism and try to do too much, too quickly.

It’s unlikely there will be any one person, entity, or solution that saves the day for humanity, but it is far more likely there can be many hands making small contributions so the collective work is made both lighter and more lasting. We must remember that what we’ve inherited and continue to build upon has been the result of a long, gradual process, shaped by limitations that we cannot fully overcome in our lifetimes—or even in future generations. This legacy is about more than just survival—it’s also deeply rooted in our sustainability, creativity, and joy.

When we reframe the narrative and view it in this way, rather than being driven by an abundance of problems we need to fix, we can be motivated instead by an abundance of meaningful choose-your-own-adventure opportunities. We all face a balancing act when trying to find the sweet spot between what we wish we could do versus what we can actually do with our time, resources, and bodies. I love dreaming of new varieties and market classes that could exist one day, but I must also acknowledge the very real limits of my own professional and personal capacity to bring those dreams alive. I pick and choose which seeds and plants to anchor myself to by way of which ones help me create a sense of place and culture that enriches my life without also consuming it. If countless other people can also carve out a little space in their lives for this, the future we leave will be as full as the one received from previous generations.

It gives me hope to see so many promising examples emerging that we can look to for ideas and inspiration. From the vaults of these gene banks and the pages of seed company catalogs, the ancient connections between humans, plants, and land are being rethread in many new and lovely forms. My worldview of possibility has greatly expanded through learning about the inspiring work happening across different pockets of the seed community.

The most accessible and powerful form of seed work I’ve seen happens when descendants of various cultures in the U.S. reconnect with the seeds and foods of their ancestors—and parallel international efforts to recover the seeds and heritage lost from their countries of origin but preserved through the immigrant diasporas to America. Additionally, community celebrations of culturally and regionally significant food crops and culinary traditions offer really meaningful ways to unite people from all walks of life to honor, preserve, and enjoy biodiversity.

The proliferation of educational resources empowering home gardeners and farmers to save their own seeds or breed their own flowers and vegetables is another beacon of hope shining a bright light on the future potential of crop diversity. With these tools, more grassroots and participatory models of crop preservation are becoming possible—including community science programs that are helping evaluate and regenerate seeds in gene bank collections, and plant breeding efforts focused on creating new crop diversity, particularly with climate adaptation in mind.

The world I hope to see us living in is one where more people are rooted in stronger connections to plants and land; the depths of the crop heritage revealed by Vavilov and others since is thriving as well as still evolving by adapting to new climates and cultures; and the human experience is rich from our love of plants. If this makes you curious and want to take more action, there are a lot of ways you can get involved, even if you can’t grow plants or save seeds personally, just being mindful of choices you can make about the food you eat and buy is a profound place to start. Support local, grow a garden, cook a meal, donate to a cause, save a seed or just savor good food.

Here’s one recipe I’ve found for activating a love of plants that anyone can try:

Step 1: Journal about a favorite food or plant memory

Step 2: Discover the evolution, history, botany, geography, and culture behind it

Step 3: Experiment with how to connect with that food or plant memory more in your life

Step 4: Remind yourself frequently why that food or plant memory is important to you

Step 5: Share that experience often with the someone else you love

May your love of plants bring your life much benefit, as well as those around you!