The Mad Agriculture Journal

It’s All Woven Together

Published on

October 23, 2025

Introduction and Interview by

Jonnah Perkins

Photos by

Beau Dahler

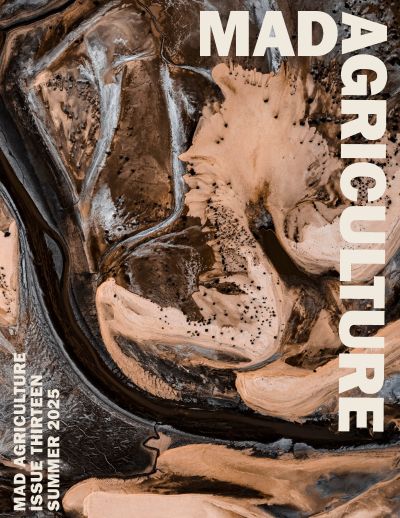

On the far northern plains of Montana, less than 50 miles from the Canadian border, I spent two days last summer with the Manuel family as they rounded up cattle, moving them from a high pasture down to a field of Kernza®. The landscape felt vast enough to swallow time—rolling grasslands broken by steep coulees, dense stands of trees, and ridgelines that catch the wind like sails. But what stayed with me wasn’t just the beauty of this place—it was the quiet choreography of a family working in rhythm with each other and the land. From the back of a four-wheeler, I watched Jody Manuel guide the herd down the slope: a calm groundedness that can only come from decades of embodied memory, passed down like a language.

Jody later told me that everything on this land is shaped by wind and water—though both arrive in extremes. “We don’t have much flat ground where we’re at,” he said. “Just coulees, and you can see the effect of weather in all of them.” The north-facing slopes, protected from the wind, are thick with grass, trees, and deeper soil, while the south-facing sides are stripped bare by sun and exposure. He sees patterns—decisions made not just by people, but by snowdrifts, prevailing winds, and the timing of microbial life. To Jody, livestock are more than production units—they’re part of a nutrient cycle that restores the thin-soiled ridgelines, building up biology where it’s needed most. Manure isn’t waste; it’s input. Movement isn’t just management; it’s fertility in motion.

From their home tucked into the eastern edge of the Golden Triangle, Crystal Manuel wakes up each morning, pours her coffee, and looks out over the foothills of the Bear Paw Mountains. “We feel incredibly blessed to live where we do,” she said. Their house overlooks a deep coulee teeming with birds and wildlife, with a clear view of the same ridges that shape their grain and grazing systems. In a region known for producing some of the highest-protein wheat in the country, Crystal sees beauty in both ecology and economy—the way hot winds harden the grain, the way arid summers imprint flavor and strength into the soil itself. This isn’t just a family farm. It’s a living generational system—each part shaping the other, season after season. Prairie Grass Ranch is the legacy of generations of Manuels. Jody humbly attributes the farm to his own father, “He built this. He did so over many decades, through what I would designate as determined grit coupled with a few divine appointments.”

Now, as Jody and Crystal’s children—Tristan, Sarah, Teague, Sawyer, Shayna, and Taliya—step into the rhythm of this place, they bring with them new questions, fresh skills, and a deep-rooted commitment to carry the story forward in their own way. I had the honor of speaking with several of them, each offering a glimpse into how legacy takes shape through lived experience. Though not all were present to share their stories, the spirit of each of them is undeniably woven into the tapestry of this farm. What follows are reflections from the next generation, each one rooted in the soil that raised them.

Jonnah Perkins, Director of Media

Teague Manuel

I’ve just always been out here, working alongside my dad and my older brothers since I can remember. I started driving tractors around ten, messing with engines even younger than that—my brother showed me how to fix stuff when I was six or seven, and I kind of took it from there. I like being home. I mean, I’ve been to Europe once, but by day two I was ready to come back. Everything was just…different. I’m not much for change. People ask if I’ll go to college, and I’ve thought about it, but I don’t really see the need. I’ve already got everything I need to know right here. I do football, school in the mornings, and then I’m out here working the pigs or helping with whatever’s needed. It’s not always the same, but that’s kind of what I like about it. I’ve tried a few different things with feeding—fermenting screenings, sprouting them, whatever I can to make it work. When stuff breaks, like the grinder, I just figure out the next best option. It’s not perfect, but it gets the pigs by. I think someday I’ll run all of this. My parents have been encouraging, but they’re not pushing me. It’s my choice, and I want it. I think I’m lucky. A lot of kids don’t get this kind of life.

Tristan Manuel

I always kind of knew I’d end up back here, even if there was a stretch where I thought otherwise. I went to school, worked a wild job with a touring illusionist, thought about being a bush pilot in Alaska—but no matter where I went, I was always coming back in the summers. This place just pulls you in. I got to see a lot of the country, lived on a bus for a while, did some weird stuff, but in the end I missed the pace of it here, the way things feel familiar but never exactly the same. Now I’ve got my own kids running around the yard, riding in the tractor with me, following calves, doing the same things I used to do. And I’m glad they can just run barefoot through the grass without me worrying about what they’re stepping in. We don’t spray, we just raise cattle the way they’re meant to be raised—on grass, moving through the land like they always have. My role? I don’t know—I’m just the guy who does whatever needs doing. Mostly cattle, a lot of equipment. My dad built this place and this herd to last, and I guess I’m just trying to carry that forward in my own way. There’s good days and bad, like anything, but being here with my family, watching the next generation start to take interest…I don’t think it gets much better than that.

Sarah Manuel

I’m a fourth-generation member of Prairie Grass Ranch, and growing up here shaped everything about how I see the world. Our family has always been close—big dinners, new recipes, everyone kind of tumbling around in the kitchen, experimenting with food. My parents are entrepreneurs in their own right, and I grew up watching them and other family members constantly build things from the ground up. That spirit of innovation was just normal to me—I never felt like I had to think inside the box. So when I started my food business, Farmer Meets Foodie, it wasn’t just about cooking—it was about creating an authentic Montana food experience rooted in the land and the people who work it. We write our menus based on what’s growing here: lentils instead of beans, oat groats instead of rice. It’s about celebrating the unsung crops that sustain this place and the soil. I launched the business in a food truck, then moved into a 100-year-old farmhouse on the ranch—an old bunkhouse that was literally dragged across the prairie decades ago because someone believed it was worth saving. That story, that sense of care and grit, it runs through everything we do. My parents gave me a place to launch, and my siblings have jumped in to help at different times—it’s all woven together. Even as we each build our own paths, we’re still rooted in something shared. That’s the beauty of it. That’s the legacy.

Sawyer Manuel

I think growing up out here, I didn’t really realize how different it was until I got older. We were homeschooled, so I had way more time to fish, to work alongside my dad, to learn things hands-on while other kids were stuck in school. I was probably five or six when I started running the tractor by myself—my foot couldn’t reach the shifter, so I had to slide to the side, reach down and shift with my hand. That kind of independence was just normal to us. And it wasn’t just about work—it was about asking questions, doing things because we believed in them, not just because that’s the way it’s always been done. That mindset came straight from my parents. They’ve never chased money; they’ve chased what’s right. And when you’re farming organically and choosing not to spray, you learn quickly that the outcomes you hope for don’t show up overnight. Farming is just gambling on a really large scale…you can think of a positive outcome in two seconds, but it takes years to get there. But now we look at some of those same fields that used to be full of weeds, and they’re flourishing. I guess that patience, that trust in what you’re building—that’s something you carry. Same with turning wrenches. I started with motorcycles when I was a kid, and that led to fixing all kinds of things. It saved me money, sure, but more than that, it gave me confidence. If something breaks, I don’t panic. I just figure it out. That’s the gift of growing up here—not just the skills, but the mindset that no matter what comes up, you can work through it.