The Mad Agriculture Journal

The Art of Feeding a Community

Published on

December 24, 2025

Written by

Carlton Turner

Photography courtesy of

Sipp Culture

Mad Agriculture Journal partnered with EcoFarm Conference to celebrate keynote speaker Carlton Turner. Featured in Mad Agriculture Journal Issue 14, this essay traces how Turner, founder of Sipp Culture, helped restore food security after his town’s grocery store closed, rebuilding community through farming, culture, and collective care.

I grew up in the small rural community of Utica, Mississippi, closer to the village of Learned or Lebanon Pinegrove Road. If pressed by a local, for more detail, I would say the Paige Grove Community. For those that don’t know the area, Utica will suffice. For those that are in the area and want a more specific relational understanding of who I am, making reference to the road might be enough, but for those that really want to know who I am and where I come from, naming the Paige Grove Community puts a geographic and cultural pin in it.

Paige Grove is the name of a church that sits 30 miles from downtown Jackson in a quiet community of dense oak wood forests and overripe pine tree farms. I grew up in the backyard of the church. It was built by my ancestors in 1873 and doubled as my grandparent’s front yard. There were no houses in between. In fact, there were no other houses within a quarter of a mile, unless you cut through the woods on a walking or horse trail.

At Grandma’s house—and make no mistake, both my grandparents lived there—but the house belonged to Epsie Broadwater Roberts. Not in deed, but in management. At her house, I was guaranteed to witness culinary bliss with astounding consistency. Her small and intimate dwelling sat on roughly two acres and included a smoke house, a chicken coop, a tater house, a pig pen, a milking pen for the cows and a slew of dog pens to house Grandaddy’s prized bird, coon, and rabbit dogs. This is the Mississippi that raised me. The Mississippi I love.

Images and ideas of rural Mississippi, both historic and present, can be really skewed from the reality that many of us experienced. Often fueled by black and white images from the Mississippi Delta in the 1950’s and 60’s, dusty roads and bare feet, the idea that Mississippi is lost in a before time rings true for some. And although some of that imagery is rooted in the lives of very real people and places, my experience was something very different.

Yes, our roads were dusty. And yes, we were poor, from an economic measure. But the community held a type of rural wealth in food and culture that has become the aspiration of many communities seeking more joy, health, sustainability, and work-life balance.

In addition to the small integrated farm where my grandparents lived, my parents owned twenty-six acres five miles away. It was on that land that I learned how to commune with the soil and produce abundance from the palm of my hands. My grandfather, Sammie Roberts Sr., would take my brother and me to the field with him and his old Ford front crank tractor to plant, tend to, and harvest peanuts, corn, sugar cane, watermelons, and sweet potatoes. In my mother’s garden next to the house, she, a 5th generation farmer, would grow tomatoes, pink-eyed purple hull peas, butter beans, squash, okra, and peppers.

Between these two houses, an intergenerational transference of cultural practice occurred. I learned how to produce abundance from the promise of a divine union. The promise between seed, soil, sun, and rain. When they come together in balance they will yield enough for everyone.

Grandma Epsie was a one-woman assembly line. She received the bounty of the animal farm, the procurement of wild game sustainably harvested from the surrounding environment, the harvests from Grandaddy’s farm production and my momma’s garden and produced 14 to20 fresh meals a week from scratch in volumes large enough to feed a family and extended community. In her time away from the kitchen she raised her ten children and tended to her elder generation and her grandchildren. She was also a builder and a gifted quilter. She never considered herself an artist. I’m not even sure if she ever uttered the word.

Growing up, I didn’t consider myself an artist either. My understanding of art was visual—drawing or painting. I didn’t have the skill to do either. I would watch my grandmother sew her patchwork collection of fabric squares and triangles into a collage of geometric patterns speaking some coded tongue that she may or may not have known, but the patterns were wired in her hands through generational transferance. IYKYK.

I sang gospel and hymns in the church choir, played trombone in the school band, and consumed all manner of jazz, funk, and R&B from my father’s vinyl collection, and early hip hop from the indie station radio shows. I still didn’t see myself as an artist. Music and food were linguistics. It was how our community said, “I love you”, and “if you need me, I’m here for you”.

There’s a difference between a cook and a culinary artist. A cook follows a recipe. I can cook. A culinary artist creates, has ten thousand plus hours of mastery in the form, has embodied the formulas of heat, acid, fat, salt, and time into combinations that produce orgasmic olfactory overload. My grandmother was a master artist.

The stories she told with her hands from raw and repurposed materials spoke to a time when the primary job was tending. Tending to family, to the land, to the animals, to the community. The culture of food, from seed to table, was the center point. All family interactions revolved around this fulcrum. I too was immersed in this practice of living within the promise.

Over the course of 30 years, this community where my family has been rooted for eight generations, which once exhibited a tangible vibrancy measured in quality engagement with your neighbors, deeply rooted in a culture of sharing and care, and a trust steeped in the belief that we were all working with each other in mind, has, not so suddenly, been reduced to a bedroom community facing food insecurity.

Consolidation of schools meant closing the two high schools that powered intergenerational engagement, stunting population growth and marked the beginning of the decline. The closing of the shirt factory meant 100 jobs vanished into the ethers overnight, the fuel for the local economy vaporized. In 2014, the local grocery store shut down. The closest grocery store is now 17 miles away.

The loss of the grocery store was acute. Community members began to question whether we were still able to consider ourselves a town if we didn’t have a grocery store.

In 2017, my wife Brandi and I, hosted our first community forum in the Westhaven Funeral Home. It was the only space we could find. We gathered a few community members along with our partners at the Gulf Coast Community Design Studio (GCCDS) to start a conversation about the future. We pinned a series of maps on the wall depicting the tri-county area. We asked the community members in attendance to map four locations: home, work, church, and market. What ensued was a conversation about what Utica once was, what has now become an unrecognizable community, and the uncertain future we now collectively face.

Our partners at GCCDS were architects and designers affiliated with the Mississippi State University’s School of Architect, Art & Design. They were housed on the Mississippi Gulf Coast helping rebuild the community after 2005’s hurricane Katrina. We partnered with this group to support the translation of community needs into community design. This session and practice became the foundation of our work to collectively reimagine our rural community around our needs and aspirations. This was the birth of the Mississippi Center for Cultural Production.

We continued to host conversations over the course of the next couple of years. At each juncture, we would ask the community about their most pressing needs. Each time we were met with the same answer—a grocery store.

It’s not easy to imagine a different future if you haven’t taken time to reconcile existing trauma. It’s like asking someone about their dreams right after they slam their finger in the car door. Trauma response trumps imagination every time. We were asking the community about the future, but the present moment presented a wealth of challenges that had not been dealt with. In order to get to the future, we had to deal with the present.

Since 2014, local leadership has been working diligently to attract a grocer to open a store in our community. But from an economic standpoint, we were no longer able to support a chain. So, we begin asking different questions. Questions about groceries, instead of about the store. We wanted to talk to the community about all the ways in which they were already producing and procuring food. Because we were almost certain that a grocery store may not be the answer.

We began using our cultural tools—focus groups, story circles, and oral histories—to unpack how our community was already producing and sharing food, and to imagine what more might be possible. We learned that our community has a rich history in agricultural production. We learned that 44% of the respondents to our randomized community survey were actively producing agricultural products for consumption. We learned that 97% of the respondents own their home and 78%, like my family, have been living in this community for multiple generations.

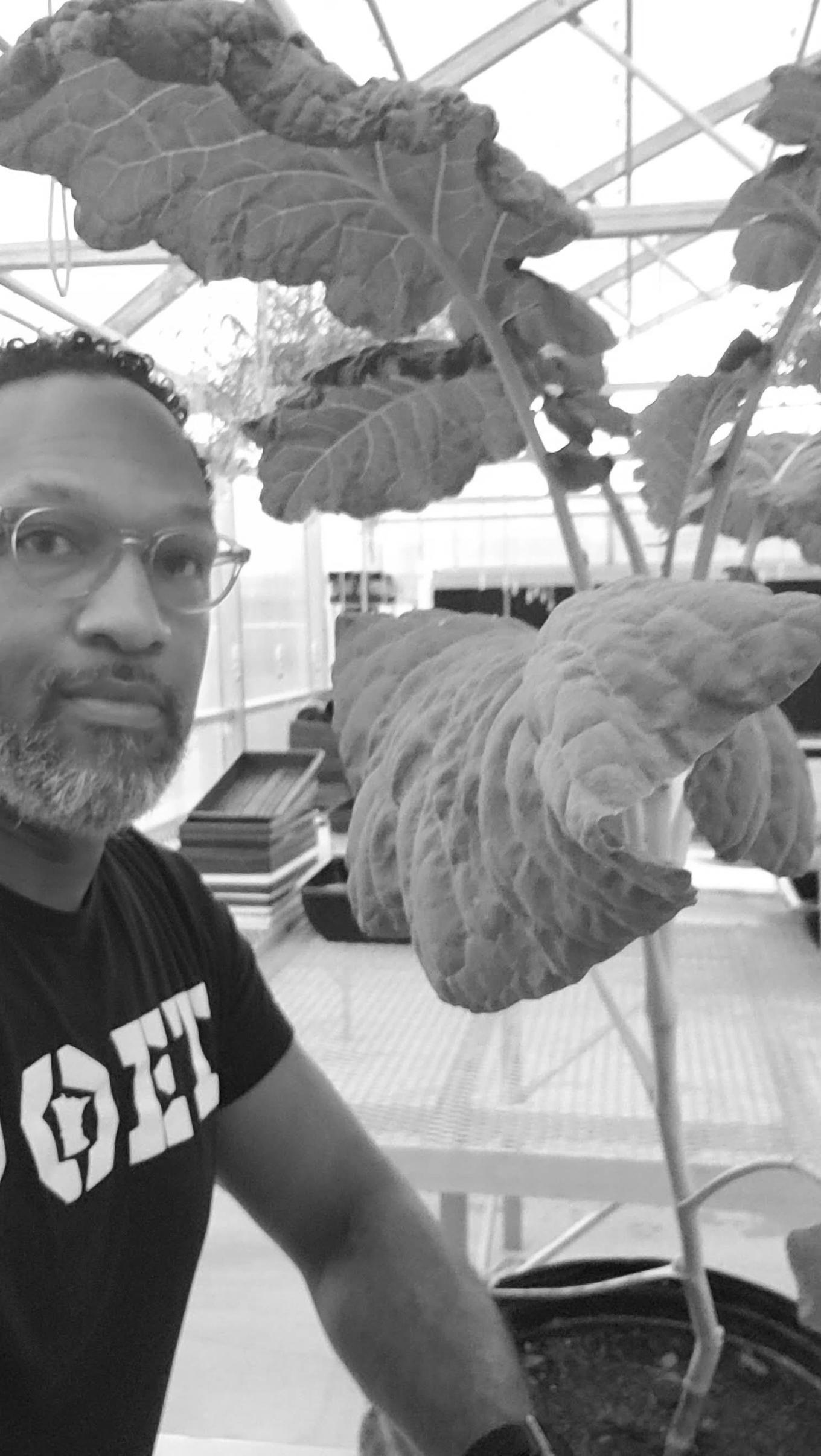

As a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many in our community planted small gardens. This was a subtle reminder that growing food is in the DNA of our people. We took the cue and opened up the Sipp Culture Community Farm on 17 acres of green space on Main Street. As part of this process, we started the Small Farm Apprentice Program to train new farmers in sustainable agricultural production. We farm on two acres using a permanent raised row structure. Our farm produces approximately 3.5 tons of food annually and employs three full-time farmers. We also have an 1800 square foot commercial greenhouse where we grow all of our starts and supply starts for several farms in the area.

In the summer of 2024, we supported the development of the Utica Food Club, a community-led resource for procuring fresh fruits and vegetables for our community. The Utica Food Club is developing into a food cooperative with aspirations to open a brick-and-mortar facility in the future.

In May, we opened the Main Street Cultural Center, a 4,000 square foot facility with a 1,700 square foot commercial kitchen and a covered sidewalk for outdoor dining and our weekly farmer’s market. This space serves as both a marketplace and a social space for our community to practice engagement and communion in a time of great divide.

We keep asking the questions and responding to the calls because we are almost certain that a grocery store is not the answer.

On Friday nights in our little town, you can now find community members sitting and enjoying a meal, singing karaoke, and members of the food club distributing produce on the corner of Main Street and White Oak at our newly opened Main Street Cultural Center. A building that has been vacant for more than 20 years is now an active community hub and home to our farmer’s market each Saturday. This seed was planted more than a decade ago. It took some time to grow, but now we are coming into our harvest season.