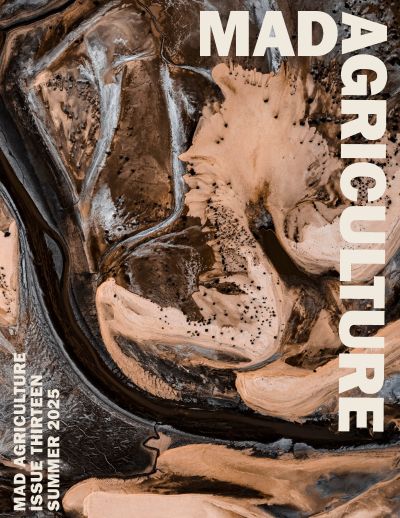

The Mad Agriculture Journal

Between the Years and the Ears

Published on

July 24, 2025

Written by

Kyle Rasch

Photos by

Brendan Davis

Introduction

Most people look forward to spring—the warmth, the soft soil, the return of life.

Apple farmers brace for it.

Even as I write this, I’m running on fumes. Sleepless weeks trying to keep flowers from freezing. Clearing cobwebs from equipment. Patching leaks. Racing to finish winter paperwork as spring barrels in. The trees don’t wait. The weather doesn’t care. Every decision feels high-stakes.

My grandfather carried this season like a duty. My father wore it like armor. And now I carry it too—but differently. I keep showing up, even when it breaks me, because I believe we can farm without losing ourselves. Because if regenerative agriculture doesn’t also regenerate the people doing the work, it won’t last.

It’s not just the farmers who are strained. The climate is shifting. The markets are tightening. The pressure is rising. We’re all being asked to find new ways forward—and fast.

The weight of spring isn’t just the weather. It’s generational.

This is the story of how my father changed. How a farm changed. And what becomes possible when we give farmers space, trust, and time to let something new take root.

It’s also a story about three brothers—each of us returning in our own way, trying to shape the next season of this land together.

Part I: When the Soil Holds Memory

I grew up in the orchard, but I didn’t plan to come back.

The farm was always present in my life—first as a playground, then as work, and eventually as something that felt too heavy to carry. My dad held it together through decades of weather, regulations, and financial uncertainty. He never talked about legacy—just survival. There was always something that needed fixing, spraying, recording. Always another loss, another deadline, another unpredictable turn in the season.

Like many farm kids, I left. There was no part of me that felt called to take over the farm. I needed space. A wider perspective. After a few failed years of college, I traveled to Australia, then worked on farms across the world through WWOOF (World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms). I learned by doing—exchanging labor for food and a place to sleep. And I saw systems that worked: food grown with care and connection, people farming in partnership with nature.

At one farm, I learned their customers understood an apple with more fungal scars meant it was healthier—the exact opposite of what I grew up with, where a blemish could sink a sale. That shook something in me.

I learned how to coax water across dry hillsides, nudging the landscape to let life return. I moved livestock with motorbikes while dodging kangaroos. I learned to grow fruit in the Himalayas. Across dozens of farms, it seemed they all shared the same mission—partnering with nature to the best of their ability.

When I came back, my dad welcomed me. He was glad to have help. But the moment he realized I didn’t return just to follow orders—that I came back to change things—tension filled the air.

Conventional agriculture was like a Lego set: predictable, mechanical, and always escalating. If a problem showed up, you just came back with a bigger hammer. It worked—until it didn’t.

He had built this iteration of the farm with his own hands, kept it alive during years that nearly broke him. And here I was—young, energized, talking about cover crops, sap testing, plant immune systems, companion planting. To him, it sounded like risk. Idealism. Even disrespect.

But I wasn’t asking him to change everything. I was just asked for space.

Well, I guess I kind of was asking him to change everything. In a way my naïve view of agriculture was passively saying everything he had built all these years wasn’t good, and was toxic to the land. That definitely wasn’t the best way to start convincing him to change.

He gave me one field on the back side of the farm—a kind of sandbox. I planted a diamond-shaped block with a chaotic mix of tree fruits. We called it Chaos. No sprays. Just observation, intention, and a willingness to let nature lead.

Some of the trees died—voles took out a few, and pests and disease wiped out most of the fruit each year. But it was never about the yield. It was about trying something different. Letting the land speak back.

Ten years later, most of those trees are still small. Some were overtaken by rootstock. It’s not tidy. It’s not commercial. But it’s where it started. We began redesigning the orchard—retraining trees, addressing pest pressure at its root, farming with biodiversity in mind.

These weren’t just technical decisions. They were expressions of values. Trying to listen more, control less.

In the beginning, it was just that—a beginning. My father didn’t believe it. But he let me try. When I became impatient, I would opt to ask for forgiveness. And while he stayed quiet, he watched.

Because even if the soil holds memory, it’s also capable of change. And though he never said it—so was he.

Part II: When the Land Begins to Listen

Change didn’t come through debates or data.

I showed him spreadsheets, studies, and videos from around the world. None of it stuck. He’d seen too many fads come and go, too many salesmen with too many promises. He didn’t need theories—he needed something to work.

So I stopped arguing and started farming.

And quietly, the land began to show him what I couldn’t.

Encouraged by what we learned from Chaos, we converted an old block of Golden Delicious apples to organic. That doubled to twenty acres the next year. Then upped it to forty. Through it all, we failed often—but learned more than we could’ve imagined.

It’s fortunate we started small, because those early lessons were critical. Trees needed time to acclimate from a synthetic system to one where they’re encouraged to defend themselves.

We saw worms pulling last year’s leaves into the soil—leaves that, if left on the surface, could carry fungal infections into the next season. That small act—nature tucking itself in—felt like a kind of healing.

With data-driven nutrition, trees showed fewer signs of fireblight and healthier growth. The soil beneath them shifted from lifeless brown to a buzzing understory of mushrooms, flowers, and pollinators—and the fruit still came. We were seeing recovery.

We had a twenty-acre block split right down the middle: ten acres conventional, ten regenerative organic. Identical varieties, planted the same year. After five seasons, the yields were starting to balance out—but the trees on the regenerative side were clearly healing. The soil’s organic matter had nearly doubled. That made an impression.

Still, I knew we were lucky.

Most farmers don’t get a break. They don’t get time to pause, reflect, or reset. They’re running from frost to fungus to financial deadline, operating from a place of scarcity, not possibility. And not because they don’t care—because they don’t have the space. The system isn’t built for it.

That’s why change is so hard. That’s why the smallest signs of healing mattered so much.

Then came the June 2023 hailstorm.

It was a rollercoaster of a day. To go from the worst drought in generations. To the most beautiful rain that nearly replenished the drought. Then in a sudden stroke of fury the sky unleashed–dropping ice up to the size of golf balls. The apples were destroyed. Some took direct hits and exploded–leaving a chunk of apple attached to the stem.

We shut down our conventional sprays to only what was necessary and mostly sprayed organic on the entire farm. When woolly apple aphids showed up, I convinced him not to spray. He hesitated, but agreed. By the time our mail-order predator lacewing eggs arrived, the lacewings and lady beetles had already moved in on their own—completely eliminating the aphids.

That was a turning point. Not because it was dramatic—but because it was undeniable.

From that moment we stopped all synthetic applications and committed all 110 acres to Regenerative Organic Certification.

Around that time, my dad began wandering into our pick-your-own events. Season after season, he started hearing families talk about how much they appreciated what we were doing.

They felt held here. Said they could taste the difference in the fruit, and smell it in the air.

They were grateful for a farm that worked with nature—where they could bring their children and feel good about what they were feeding them.

It wasn’t one moment. It was the culmination of many seasons. And slowly, something began to click.

He started repeating those stories to our family. Then defending our practices. Then proudly describing organic farming.

And it wasn’t just customers—it was peers. At first, they raised eyebrows. Then they started asking questions. Eventually, they began showing curiosity. Even researchers wanted to know what we were doing.

It wasn’t fast. But it was real. And it stuck.

That’s how farmers change. Not because they’re told to—but because the land starts to make sense in a new way. Because it becomes personal.

By the time he began telling our story in his own words, I knew something had shifted.

And that’s when we realized: we were entering something new—a phase of shared trust, co-creation, and change.

Part III: When the Trees Speak Back

We named the farm Third Leaf Farm because it marked a moment.

In the life of a tree, the third leaf is when it begins to bear fruit. The roots have settled. The shoots have reached upward. And something new is finally ready to be offered. That’s us—three generations deep, in our third iteration, beginning to see what might be possible if we keep going.

The first leaf was planting deep roots—my grandfather’s time. Building something from scratch. Diversified. Trying, failing, trying again. Farming because it was a way to feed the family and build a life. Because it was honest work, even if it was backbreaking.

The second was scale—my father’s era. Efficiency, markets, chemical inputs, big goals. The name of the game was keep up or get out. And somehow, through the chaos of the ’90s and 2000s, he kept the farm alive while neighbors disappeared one by one.

Now comes the third. The part where something new begins to emerge. A blending of old and new. Where tradition and innovation don’t cancel each other out—but find a way to coexist.

But none of it means much if we don’t also take care of the people doing the work.

My grandfather—though he can no longer walk the orchard—still drives through it slowly, windows down, watching the trees like they’re old friends. He doesn’t say much these days. But when he does, it’s often a story from the old orchard. About a time they planted strawberries just beneath the apple trees. Or the extension agents who taught him about soil health.

Some of the oldest trees we have today—now around fifty years old—were just being planted as he was passing the responsibility to my father. That quiet transition marked a shift in caretakers, and the roots laid down then are still holding the soil today.

He’s the one who reminds me: you can’t take the farm out of the farmer.

My dad is still here. He still drives the rows, checking the leaves with the instinct only decades can teach. But he’s starting to slow down. Starting to trust the path we’re on. Starting to let go.

He’s even talking about going fishing this weekend—during one of the busiest weeks of the year. That may not seem like much. But for him, it’s huge for a farmer.

And me—I’m trying too. Trying to be another kind of farmer. To carve out time to keep friendships alive, build a clay teapot, or have a jam session with my brothers. It’s not easy. The task list never ends. And farming culture doesn’t exactly celebrate rest. I know farmers who rarely sleep. As I write this in early May, I look at the ghost in the mirror and I too am that farmer.

That’s the next part of this journey: how to regenerate the farmer.

We’ve built a system that demands everything, rewards little, and praises exhaustion as virtue. In any other profession, that level of sacrifice would make you a hero. On the farm, it barely gets you by. Still, we keep showing up. Because we love the land. Because we care about feeding people. Because we are concerned about the direction this ship is sinking.

But I believe another story is possible.

One where farmers are supported by their communities. Where neighbors become part of the process. Where farms open their doors and say, “Come see what we’re building.” Not just with healing food, but with healing relationships.

Because regeneration doesn’t end in the soil. It extends to the soul.

Now, we’re building networks. Collaborating with local universities. Hosting trials. Gathering data. Using science not to gatekeep, but to open doors. In this world data builds trust. And trust makes transformation possible.

My two brothers are back on the farm now—Eric, our beekeeper, and Devin, our overqualified analytical chemist. We’re figuring it out together. Leaning on each other. Telling the story honestly. Trying to breathe into something better—not just for us, but for those who come after.

Some days we move fast. Other days we just stand quietly in the rows, listening.

The trees speak back. If you’re quiet long enough, they’ll tell you what you need to know.

And now they’re telling us to keep going.

But what does it mean to keep going—in a world that keeps pulling us apart?

Closing: An Invitation

Wendell Berry once wrote:

“We seem to have been living for a long time on the assumption that we can safely deal with parts, leaving the whole to take care of itself. But now the news from everywhere is that we have to begin gathering up the scattered pieces, figuring out where they belong, and putting them back together.”

That’s what we’re doing here. Gathering the pieces. The soil. The story. The relationships. The wisdom.

People ask me all the time—other farmers, customers, friends—how do we start? How do we make it through? How do we keep going when the system doesn’t seem to support the direction we’re heading?

And honestly, I don’t always know. But I usually say something like this:

Start small. Listen. Don’t worry about being perfect. Get curious. Find someone doing something different and ask them questions. Maybe you visit their farm in the off-season. Maybe you call them when you’re stuck. Maybe you try something different this year and see what happens. That’s how I started. That’s how most of us start.

When customers ask what it means to support regenerative agriculture, I tell them it begins with caring. With showing up. With asking the story behind your food—not just the practices, but the people. It doesn’t have to be fancy. Just real. Relationships, not transactions.

When fellow farmers ask if this path is worth it, I tell them: we’re still learning. But we’re not alone. And for the first time in a long time, it feels like we’re building something that can last—not just in the soil, but in our lives.

I didn’t know this would be my path. But I’m glad to be here.

On this land. In this season. Planting trees for whoever I’m borrowing this land from—and for whoever comes after.