The Mad Agriculture Journal

Farming with Water, Not Against It

Published on

July 08, 2022

Written by

Jonnah Mellenthin Perkins

Photos by

Jonnah Mellenthin Perkins & Jesse Perkins

Water always wins, eventually. Moving water, holding water, stopping water, and redirecting water is an integral part of agriculture. Humans have shaped their lives around their capacity to control water. In my region of the Midwest, the challenge is both too much water and not enough — often in the same growing season.

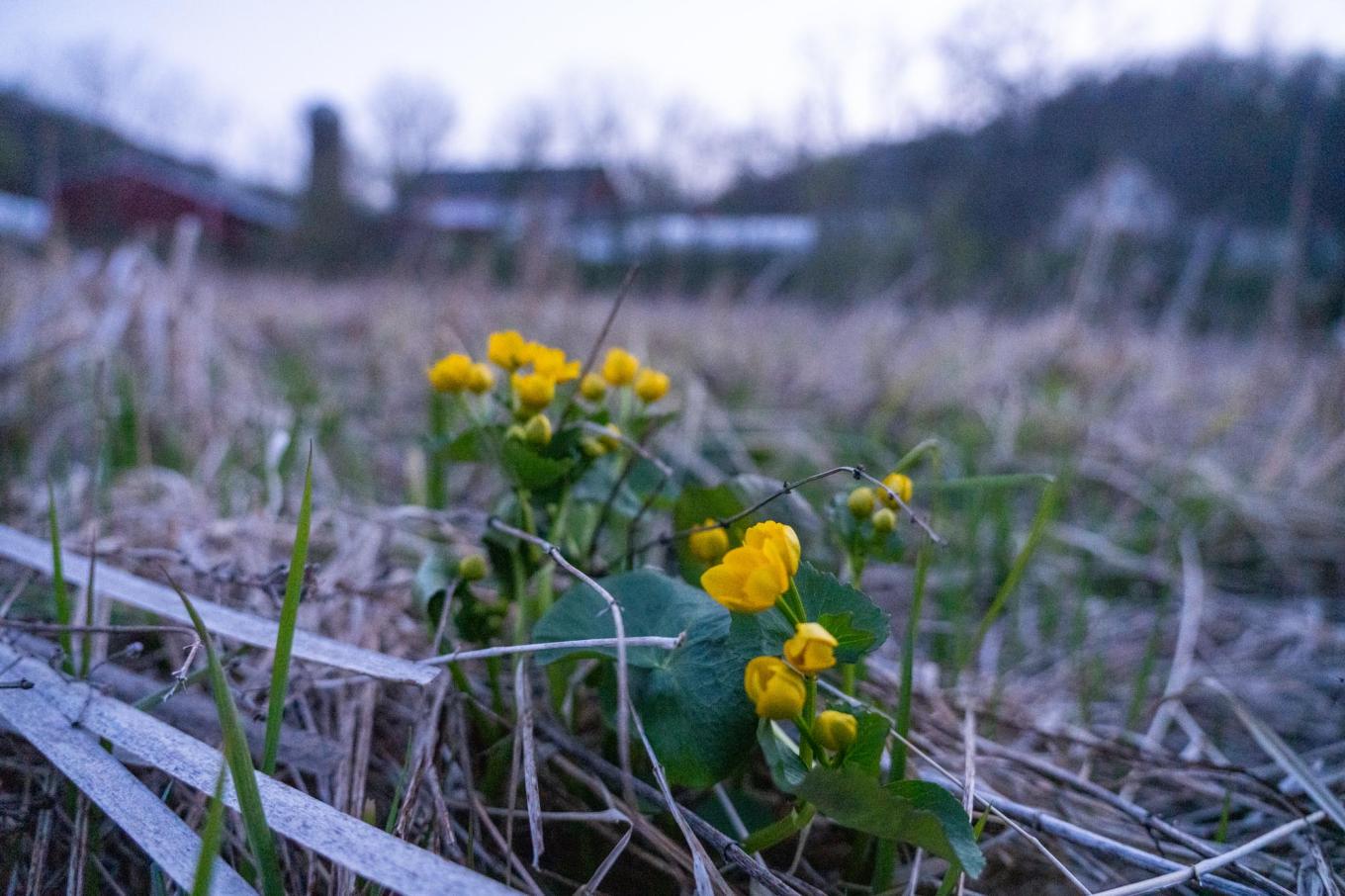

When I first moved to rural southwest Wisconsin in 2007 to work on my boyfriend’s family farm, I had no concept of what I now know as resource management — the moving and shaping of land, water, minerals, plants, animals and wind. One of my first jobs was harvesting watercress from the farm’s wetland for our Spring CSA delivery. Knee deep in muck, I reached out my clean hand to hold fistfuls of bright green cress that I sliced with my knived hand. This seemed like a quaint job for a fast-paced, high volume, community supported agriculture farm, and I loved everything about it. Vermont Valley Community Farm was one of the largest CSAs in the nation, delivering solely what was grown on the farm to thousands of families in the Madison area. As a 24 year-old with no experience in agriculture, harvesting wild food adjacent to fields where I had transplanted broccoli that same day was completely lost on me. It didn’t occur to me until years later, what an incredible service the wetland was providing the farm.

Our farm has transitioned away from CSA work, and we now focus on organic seed potato production, bringing what had been a side business to the forefront of our work with our new farm name, Mythic Farm. On the eastern edge of the Driftless Region, the roughly 24,000 square mile tract of unglaciated land at the intersection of Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota, and Illinois, we are at the confluence of multiple ecosystems: oak savannah, eastern tallgrass prairie, wooded wetlands beneath valley slopes with rich silty loam soil. Water that bubbles up from the limestone bedrock upstream flows through our farm on its way to the Wisconsin River before emptying into the Mississippi and then into the Gulf of Mexico.

Vermont Valley Community Farm had fully integrated the 32 acre wetland into field planning long before I became involved in the farm, but it took me years to fully understand the scale of its importance. While I like to give most farmers the benefit of the doubt about putting conservation first, every decision needs to be made in financial reality. Farming is a speculative enterprise that is based mostly on variables outside of the farmer’s control. Our wetland is a financial stopgap first, and an altruistic work of conservation beyond that.

A history of tilling, filling and felling

European settlers began farming in this area after the Civil War, bringing with them land management techniques that caused decades, if not generations, of acute challenges. Over the years hillsides were cleared for grazing and wetlands were drained and filled to create more fields. These changes turned “unproductive land” into usable agricultural land, but at a high cost. Removing the wetlands and overgrazing hillsides took away the natural defenses of an already flood prone area.

In the Driftless region, the prairie root structures, deciduous forest, and wetlands that held soil, water, and wildlife habitat for millenia were folded and crumpled up into a slurry of destruction in the name of agricultural engineering. In the ecological game of rock, paper, scissors that is played out in farming innovation around the world, water always comes in to show where food can really be grown.

Water is never far away

Our first child was born in December of 2011 — perfect timing for a vegetable farm baby. The winter was full of days that crossed into nights that crossed back into days rocking my son Paavo next to the wood burning stove. By spring we were ready to emerge from our cozy warren to work in the greenhouse. By summer, it was clear that we were in a drought year. If you are a midwest farmer and have been in this business for at least a decade, then you will remember 2012, the year that ended so many small farms across the region.

The Driftless has no natural lakes, water is either moving or it is underground. Underlying sandstone and limestone geology give way to thousands of springs that pop up when the water table is high. When water is low, it is still sitting right below the surface, and in our case, flowing just next to our fields. My husband Jesse slept about as much as I did that summer, setting 2am alarms to move irrigation systems.

The gift of farming at the edge of water is having it close by when it’s needed. The challenge is that you can’t take it away. But what I learned from our wetland is that she holds the water when there’s too much, for when there’s not enough.

Sharing with fauna

Our wetland is home to waterfowl, beavers, sandhill cranes, raccoons and deer. The territory of these creatures doesn’t stop at the banks of the marsh grass, it extends into our fields. Deer fencing doesn’t keep out cranes and scarecrows don’t scare away racoons. Losses to animals have never been catastrophic and we have learned to share the stories of our rich biodiversity. Afterall, the farm passes through the wetland, not the other way around.

Wetland as flood mitigation

In June 2016, water from the Blue Mounds Creek, the small river that serpentines through our wetland, swelled over the road. The muddy water roared just inches from the underside of the bridge that connects us to fields across the wetland. The challenge for us wasn’t watching crops go underwater, it was getting to the field to harvest. Driving the 20 minute detour on highway roads was a real logistic to manage with a crew in the open bed of a pick up truck, but we had been saved by the expansive capacity of the wetland.

Too much rain isn’t a good thing on our farm. It puts field work on hold, it creates conditions for disease, mosquitos hatch, and humidity is uncomfortable. But farming next to a living sponge has given us the ability to keep our farm above water while the region faces crop loss at a ballooning rate.

Farmers are at the forefront of our changing climate. In the geological blink of an eye, we have moved into an epoch where much of our agricultural land will shift into no longer being productive. This is where farming with water is so important. And in some regions, learning to farm with less.