The Mad Agriculture Journal

Perennial Potential

Published on

July 08, 2022

Written by

Omar de Kok-Mercado

Photos by

Omar de Kok-Mercado

Iowa was once a perennial oasis of tallgrass prairie, wetlands, and oak savannas. Those ultra-diverse ecosystems supported abundant people and wildlife and provided essential regulation and provisioning services, such as purifying air and water, sequestering carbon, and mitigating climate. Less than a tenth of a percent of remnant prairie remains, and oak savannas are one of the most endangered ecosystems in the world.

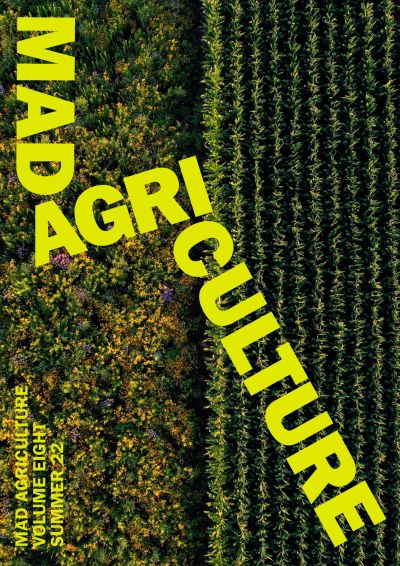

Now, the Iowan landscape is dominated by two major monoculture crops—corn and soybeans—that grow for approximately 27% of the year. The result is we’ve lost ecosystem functionality in the state. Iowan soils are degraded and even after nine years of the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy, water quality has not improved—and in some cases it has worsened.

Science has demonstrated that undiversified monoculture production systems do not provide robust ecosystem services and have negative effects on people, wildlife, and ecosystem functionality. In contrast, the water running off a prairie runs clear, birdsongs fill the air, and insects buzz with delight as they pollinate flowers.

Making changes to the row crop production system is a difficult sell because row crop farmers have enormous capital investments in their equipment. The industrial infrastructure to process grain has also become a modern marvel of will and engineering, costing billions of dollars. A solution that couples agricultural production with robust ecosystem services is the strategic integration of prairie into row crop fields.

The prairie strips conservation practice was pioneered at Iowa State University and has now grown to cover 14,000+ acres in 14 states thanks to prairie strips being eligible for cost-share via the USDA Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), CP-43.

Integrating prairie where water enters and exits the field, alongside waterways, in a terrace channel, or through the field in widths that are conducive to farming equipment, provides disproportionate benefits. Studies at Iowa State demonstrated that when 10% of a no-till row crop field was transitioned to a diverse mix of native prairie grasses and forbs, it reduced soil erosion by 95%, increased bird abundance two-fold and pollinator abundance three-fold. The diversity of the prairie is reflected in the ways that prairie can benefit wildlife, people, and our society.

Prairie strips also enhance soil health, sequester carbon, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, reduce water runoff, and increase soil organic matter. The prairie strips practice can pay by converting marginal and sub-profitable row crop acres to prairie. Every farm has acres not suited to row crop production, and not investing inputs on acres that are not yielding is just business.

Thankfully, prairie strips are one of the most cost-effective conservation practices—especially when coupled with the CRP cost-share, which offers no out-of-pocket costs for installation and establishment. If you want to make a positive environmental impact, prairie has got the whole kit and kaboodle—a big bang for a little buck.

Prairie strips are also a stepping stone to habitat connectivity. The benefits to the larger community come in working together and blurring the lines between farm fields—you can connect your prairie strip to your neighbor’s, and so on. Watch that prairie strip grow into a long road and disappear into the horizon. Using prairie and other perennials—like trees and shrubs—to connect agricultural infrastructure can revolutionize how farms are laid out and designed in the Midwest, setting the stage for stacking regenerative enterprises.

Expanding on prairie strips by integrating trees mimics the oak savanna ecosystem structure —one of the most diverse ecosystems in the world. Using oak savannas as the model, the understory could produce forages for grazing livestock, and the canopy and mid-story tree crops could produce fruits, nuts, and timber while providing shade for livestock. Now, you have the building blocks for one of the most powerful agricultural strategies to mitigate climate: silvopasture.

Constructing perennial corridors that connect to existing livestock processing and packing facilities would allow for livestock to walk through the corridor rather than be loaded on trucks and transported. As livestock move through the corridor (guided by virtual fencing), they could also take temporary residence in an existing monoslope, and the manure produced could be incorporated into an anaerobic digester that produces renewable natural gas.

While the livestock are in the monoslope, they might as well graze on cover crops in adjacent row crop fields and bring along mobile solar arrays. These could collect and store water, provide shade, generate local broadband, serve as an IoT hub for remote sensing technology, and produce energy that can be stored and then tied into the grid.

The diversity of crops grown in these perennial corridors will need to mirror the diversity of expertise necessary for a complex system like this to work. To me, that’s the most exciting piece of this vision—that diversity on the land means diversity in people. If the prairies and savannas of Iowa can teach us one thing, it’s that perennial diversity equals resiliency, and being resilient is just good business.

Incremental change in agriculture is not enough. Monoculture fields are a blank canvas. Embrace complexity. Plant natives and integrate livestock.