The Mad Agriculture Journal

The New Gaucho

Published on

September 19, 2025

Written by

Felipe Urioste

Photographs by

Guillermo Fernandez

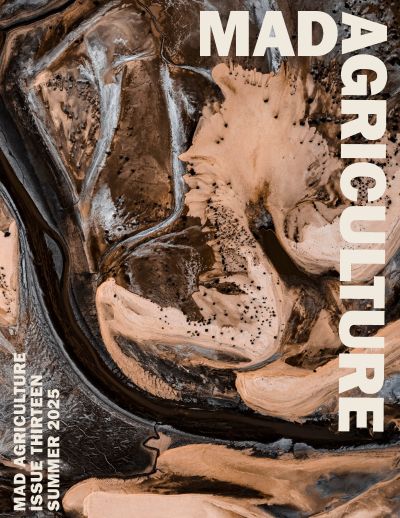

Ramiro García Pintos and the Revival of Regenerative Tradition

In the heart of rural Uruguay, where the land ripples in soft rolling hills covered in native grasses and the horizon stretches unhurried, lies Reboledo. A town in the Uruguayan department of Florida, that, like so many others in the Uruguayan countryside, holds within its people a quiet wisdom—passed down through mate, horses, and generations. This is the home of Ramiro García Pintos. This is where the contemporary gaucho emerged—without ever truly leaving—a new kind of steward: one who sees the land as a living organism, who plans his grazing as if sowing the future, and who understands his role not just as a food producer, but as an active agent of ecological regeneration.

A Landscape Shaped by Grazing

The landscape surrounding Florida—like much of Uruguay—is far more than a green field. It is one of the most diverse and best-preserved grasslands in the world. It is not empty land awaiting cultivation, but a living web of grasses, legumes, insects, birds, and microorganisms that play critical roles in carbon capture, water infiltration, soil fertility, and biodiversity.

These grasslands didn’t arise by chance: they evolved in balance with the movement of herbivores that roamed in herds for thousands of years—grazing, trampling, fertilizing, and then allowing the land to rest. Grazing was a natural part of the cycle. When those animals disappeared; cattle introduced by humans took on that ecological role. But modern livestock management—often continuous and unplanned—broke that balance.

Ramiro understands the cycles of grassland ecology. That’s why he implements Holistic Planned Grazing on his land—a method that seeks to mimic those natural rhythms while considering the entire production system: soil, plants, animals, climate, and people. He moves animals with precision, in defined times and spaces, and then gives the land the rest it needs to recover. In doing so, instead of degrading the land, livestock regenerates it. Instead of erosion, it brings strength.

A Culture in Transformation

Beef is part of the Uruguayan DNA. Asado is not just food—it’s gathering, it’s identity. But that culture is also evolving. Today, consumers—particularly in the U.S. and Europe—are asking deeper questions about where their food comes from. They want to know not only who raised their beef, but how. What was the impact on the land? On the water? On the animals? On the people?

In Uruguay, a country known for its pristine grasslands and beef exports, this shift is more than a marketing challenge—it’s a cultural inflection point.

For generations, Uruguay and the Pampas region of Argentina have been home to cattle raised entirely on grass. These ecosystems evolved with the rhythm of grazing herds, and cattle simply stepped into that role. But with the arrival of feedlots, industrial corn and soybean packages, and the imported promise of “modern efficiency,” something shifted. Grass-fed beef—once the norm—was painted as inferior: less tender, less profitable, less modern.

And yet, Uruguay never went all the way. The feedlot model, while present, did not overtake the nation’s pastoral traditions the way it did in the U.S. That hesitation—perhaps born of cultural instinct, perhaps geography—now offers a unique opportunity. With the right policies and incentives, Uruguay could return fully to its roots—and advance them. Not as a step back, but a step forward: into regeneration.

Across Latin America, many still look to the United States for signals of development and business innovation. But what if leadership today means something else entirely? What if the true mark of progress lies not in scaling extractive models, but in restoring the ones that work?

In that context, Ramiro not only cares for the land—he opens it up. He welcomes researchers, brands, and consumers. He sits at tables discussing global sustainability with the same ease as he sits on a stone, sipping mate in the shade.

Ramiro, like many other regenerative producers, is part of a movement that is no longer on the margins. They are emerging as the new leaders of ecological regeneration—those who understand that the path to addressing the climate and biodiversity crises may begin with something as simple, and as complex, as photosynthesis and planned grazing.

A Path Across the World

Like many young people from rural areas, Ramiro had to leave his town to study at University in Montevideo. The shift was abrupt: from open fields to concrete, from the rhythm of the horse to the pace of the city. But he never stopped looking back to the countryside. His vocation was always clear.

Later, his path took him to Australia, where he worked across farms in various regions: bushes, semi-arid zones, and mixed landscapes. During long harvest days in Western Australia, he came across an audiobook that resonated deeply: Holistic Management by Allan Savory, the African ecologist. It offered a grounded, common-sense perspective on agriculture—one that reflected Ramiro’s own experiences and suggested a path worth exploring.

The concepts in Savory’s work gradually took root in Ramiro, reinforcing the idea that this was, as the book’s title suggested, a revolution in common sense—a more thoughtful and coherent way of doing what had traditionally been done back home. The land should be managed with respect and in sync with nature. In Savory’s words, Ramiro found structure—a framework that honored both ecological rhythms and human intuition.

Today, Ramiro is the director of Pampa Oriental, the Savory Institute Hub in Uruguay. From this platform, he works to restore the health and productivity of Uruguay’s grasslands by supporting producers who want to transition toward regenerative practices—ones that are ecologically sound, socially responsible, and economically viable.

Pampa Oriental is not just an institution—it’s a growing movement, made up of young agronomists and seasoned ranchers, walking the land together. They offer not prescriptions, but partnerships: long conversations over mate, quiet observation in the fields, and collaborative planning rooted in Holistic Planned Grazing. Their approach blends ancestral knowledge with ecological science—particularly through tools like Ecological Outcome Verification (EOV), which monitors how the land responds to these changes over time.

Currently, Pampa Oriental works with more than 200 producers across over 500,000 hectares. Their goal is not simply to train, but to inspire—to help producers see themselves not just as suppliers, but as stewards. Not just as managers, but as regenerators.

A Man of the Land, Grounded

Despite his travels, readings, and presence in international meetings, Ramiro remains deeply

connected to rural workers. He understands them, respects them, and listens—seeking to learn from traditional wisdom and from customs at risk of being lost. Just as he listens to people, he listens to the land, attentive to what the soil has to say and ready to respond through action.

When he rides through the fields on horseback, it’s not for show. It’s because that’s where he belongs. Because there, among the grass and the animals, he feels whole. No title, no stage, no recognition is worth more than the silence of a well-managed afternoon on the land.

Mate, Hat, and Purpose

Ramiro hasn’t abandoned the traditional forms of the gaucho: he drinks mate at sunrise, shields himself with his hat when the wind picks up, and strokes the flank of his horse like a brother. But there’s something in his presence that signals a broader perspective. He knows his role is no longer just to care for livestock—it’s to safeguard water cycles, protect soils, restore biodiversity, and at the same time, produce beef.

Because yes—the new gaucho produces. But he produces with awareness. Produces without sacrifice. Produces to nourish, but also to heal.

No one knows the land better than a horse. Ramiro understands this. His bond with horses is not one of dominance, but of partnership. From a young age, he learned to read their gestures, to feel their rhythm. Today, he still rides his fields on horseback—not out of romanticism, but because the view from the saddle is sharper. The animals are better understood and time is more respected.

And it connects him with something more ancestral. The horse reminds the gaucho of his humanity, his fragility, and his place in a world that owes him nothing.

Not Nostalgia—Evolution

The gaucho never disappeared. He transformed. And in that transformation, he gained strength. Today, the new gaucho—like Ramiro—is not just a symbol of freedom: he is a symbol of hope. He represents a generation of producers who understand that land is not a resource, but a legacy. That production doesn’t have to mean destroying. And that in the grass, in the dung, in the slow rhythm of the horse, might lie the key to confronting the greatest crises of our time.