The Mad Agriculture Journal

Bringing Farmers to the Table for Conversations about River Health

Published on

November 12, 2021

Written by

Emily Payne

In Collaboration with

River Network

Photos by

Lauren Harper

“I’m sick of the D word,” says Kyler Brown. As a small farmer and rancher in Del Norte, Colorado, he spends a lot of time talking about drought. “To say you’re in a drought of 19 or 20 years, it seems like you’re not in a drought anymore.”

In 2020, U.S. officials designated 100 percent of Colorado as abnormally dry or under drought. A wet spring relieved about half of the state, but west of the Continental Divide, severe conditions have only gotten worse. About one third of Colorado remains in extreme drought and 15 percent is in exceptional drought. Scientists are labeling parts of western Colorado a climate hotspot, an area in “mega-crisis.”

This year, the U.S. government declared a water shortage for the first time ever on the Colorado River. The thousands of farmers and ranchers relying on the state’s river system are some of the first and hardest hit by the unprecedented challenge.

“It used to snow in the winters and rain in the summers. Now, it just rains in the winter and that’s about it. It’s putting a lot of strain on the ability to produce anything,” says Ben Wolcott of Wolcott Ranch in Mancos, a small town 30 miles west of Durango. For the last three years, his ranch has seen between three and six inches of precipitation a year—less than the Chihuahuan desert.

Ben’s grandfather used to run cattle with minimal irrigation at Wolcott Ranch. The summer rains would come in around 2pm every day and soak the land for two hours. It was typical to lose a few cows to lightning during those times. But in the last decade, Ben says, both the lightning and the rain have stopped. Irrigation is critical now, especially in the summer.

Colorado’s shorter, drier, and more mild winter seasons are also killing fewer pests. “We now have many of the same disease pressures that other places like Idaho or Montana do, and we used to never have, because our winters were so tough,” Kyler explains. Weeds are becoming harder to manage, as they’re all that want to grow in extreme drought conditions.

These new pressures are straining already thin margins and limited time, labor, and resources. Season after season, producers must treat more symptoms while the root problems are only getting worse.

“Some people just throw up their hands and say, ‘I’m going to pump water as long as I can pump it, and when I get shut down, I get shut down,’” Kyler says. “But it’s pretty hard to outrun a climate crisis.”

Strong feelings about water use are built into the DNA of the semi-arid western slope. Farmers and ranchers are Colorado’s largest water users, but they’re typically underrepresented in local Stream or Integrated Water Management Plans (SMP/IWMP). According to Kyler and Ben, producers such as themselves need to be leading these conversations.

SMPs can serve as a win-win: producers access capital while addressing water flow and quality issues for the wider community. Farmers and ranchers can also use SMPs to request financial assistance, influence state and local management decisions, and attract partnerships for larger farm restoration projects. The projects are heavily supported by NGOs like the River Network, which provides technical assistance and facilitates a peer learning network to support those leading local efforts.

“River quality and river quantity affect farmers’ and ranchers’ livelihood probably more directly than almost anything else,” Kyler says, and conserving this resource necessitates working together. “The weeds your neighbor has, you have. The ditchwater that they don’t have doesn’t get tailwater to you…that’s just how it works.”

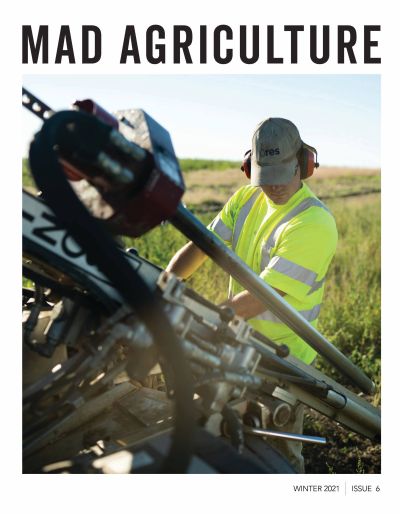

Kyler is protecting river health on his own farm by replacing old and inefficient diversion structures. This has reduced maintenance, improved diversion efficiency, and reduced erosion on the farm while improving both water quality and wildlife habitat. But this outcome isn’t possible without cooperation across the community, Kyler emphasizes. The work—called the Five Ditches Project—was led by the San Luis Valley non-profit Rio Grande Headwaters Restoration Project, but water resource boards, landowners, non-profit groups, and the Natural Resources Conservation Service all played a role in its success.

Ben and Kyler often see a disconnect between those farming the land and those leading projects. Producers either can’t afford time away from the farm to attend community meetings, or they aren’t aware of the meetings to begin with.

Those who work on water full-time for a non-profit or the government, for example, come to meetings with a much different perspective than the farmers working the fields: “If you are someone who gets paid to wear a polo shirt with a logo on it…and you don’t ever spend any time actually producing a crop, it seems very straightforward for you to say, ‘You should just jump on a 2:00 PM Zoom call and be a part of the round table,’” Kyler says.

Advocacy efforts fall flat without meaningful, trusting relationships, according to Kyler, and those take time and energy to build.

“There are a lot of people like me that would love to farm and ranch just a tiny bit different, or a little bit better, but we feel trapped in some really tight margins, and some historical practices,” he says.

For Kyler, these conversations are not only about river conservation but protecting rural communities. He thinks policies with incentive programs can be mutually beneficial for both producers and the environment: “paying farmers and ranchers to not only have more in their pocket so their rural communities don’t just get stripped away, but also have a better environment, wildlife, and more.”

Kyler encourages tough conversations about water by engaging with the media and his neighbors. “It’s one of the few things that I’m willing to stick my neck out on,” he says. He works with the Rocky Mountain Farmers’ Union and wrote an article on water conservation for High Country News.

Ben speaks directly to his peers, as well, by emailing, texting, calling, and traveling to farms and ranches to talk about conservation opportunities. He also serves as an Agricultural Consultant for the Mancos Conservation District.

Looking ahead, Ben and Kyler think that more mutually beneficial solutions are possible with open-minded and creative thinking. This means focusing on shared goals, rather than labels and identities, and thinking outside of the box of what’s been done before.

“Whether it’s about regenerative ag, or water policy, or where animal rights fit in, there’s just a whole list of things that are all coming down the barrel,” Kyler says. “How many different ways are there to get some similar results, as well as some new ideas, and not just put on our team jersey and say, ‘Yay me’?”

“These are not different groups of people,” Ben agrees. “We all want the same things.”

The thousands of producers that depend on Colorado’s rivers need to not only work together but work with nature itself, according to Ben and Kyler. Most importantly, farmers need to be physically at the table for conversations about water management.

“As a steward of the land and water, and as a rancher, it’s part of my duty to care and actually take action. That’s part of the job description,” Ben says. “Agricultural producers have everything to lose or gain by [river health]…Planning for the future of agriculture and our rivers is important enough that it deserves my time.”

Producers can learn more about how to get involved in their local SMP or IWMP, including how to participate in community meetings, by visiting www.ColoradoSMP.org.