The Mad Agriculture Journal

Landscape is the Future: Agriculture as Artform

Published on

November 12, 2021

Written by

Jacques Abelman, Maureen Hearty & Kirsten Stoltz

Photos by

Jacques Abelman

Agriculture could be considered the first fundamental human act of making a mark on the land. This act of drawing upon the earth with the language of the furrow, the digging stick and the plow has always existed in order to draw forth fertile yields of grain, vegetable and fruit. In that sense agriculture is an artform uniting us with the land.

The earthen drawings of agriculture have called forth sustenance out of the soil for at least ten thousand years in a complex interchange built on the relationships between seed and soil, hand and tool. Today, this ancient exchange is fraught with tensions and perilous complexities. Machines have multiplied the plow’s capacity a million times, drawing ever more resources out of the earth to the point of ecosystem exhaustion. New pressures and rapidly changing environmental conditions have brought this historic dialogue to a critical point. Humans must now question the validity of its current relationship with the planet and perhaps reexamine with a questioning eye the drawings inscribed on our living landscape.

These tensions are brought into sharp relief perhaps nowhere as critically as the American West, where center pivot irrigation creates a graphic and dotted landscape. This architecture of crop circles is imposed on the land stretching for countless miles. Industrialized monoculture draws ever more life from the soil in an intensive extraction which shouts more corn, more wheat, more more more…

Agriculture remains a great artform, one that has shaped the West and specifically the eastern Colorado High Plains. The practice of hand drawing in the earth, exposes questions; “What new realities are possible here today and for the future? What new drawings could take shape?” The Prairie Futures project exists for this purpose.

At the simplest level, Prairie Futures takes the lexicon of crop circle, farm house, and furrow as a starting point. Bring the hand back into the dance, drawing our furrows with string and using traditional tools and shaping spaces to a human scale. The old farmhouse of the High Plains has

been deconstructed into a series of outdoor rooms which welcome the public into the project. The crop circles are edged and aligned, creating a pleasing space where one navigates easily through the site, bringing visitors into the heart of each circle and into close contact with the

cultivated plants. Hemp, Millet, Amaranth, Quinoa, Sunchoke form the bodies of these installations, plants that are regionally under-utilized but which have been selected because of the low ecological impacts they have upon the land. Sourced from around the world, these crops have proven to be water smart, nutrient dense, and economically promising. Accompanied by native companion plants sourced from the indigenous short grass prairie, they are the “future” in Prairie Futures.

Seeing Joes

On the outskirts of high culture and urban centers exists the rooted joys and folk cultures of the everyday. The Prairie Futures project in Joes, Colorado challenges the boundaries of fine arts practices and begins to expand the American vernacular by bending rural craft-centric stereotypes towards contemporary landscape design, social engagement and climate activism. When revealing artistic possibilities, local subject matter and historical framing is paramount to engaging rural communities and artists must provide activation to find collective and connected expressions. The Liberty Rural Learning Cooperative (LRLC) organization seeks to expand an independent rural visual language and explore interrelationships between history, mythmaking and storytelling. Through its project, Prairie Futures, the LRLC uses networked art practices to expand the power of artwork made in the region. Widening the cultural infrastructure to be supportive of place, community and rural context.

Joes Colorado (pop. 80) was once a popular first stop for travelers coming to Colorado along Highway 36 from the midwest, but as the interstate was built across the US, recreational travel along small highways was all but abandoned. Since, a series of tiny, self-contained towns formed across the high plains landscape. Survival of the fittest was, and still is, in many towns’ psyche. Ideas of consolidation, sustainability and alternatives have led to anxiety, dissolving the rural DIY spirit into Dollar Store fool’s gold. Western expansion has left Colorado’s peoples, land, air and water forever altered in unnatural ways and a recalibration is needed.

Since 2016, renewed cultural engagement has flourished in Joes as a collective of local citizens officially organized as the Liberty Rural Learning Cooperative (LRLC) and began working to broaden arts and cultural activities in the region. Upon entering Joes, visitors come upon the Prairie Futures site, between the liquor store and the old church, on the Benton family homestead. Matriarch Mabel Bond Benton came to eastern Colorado around 1915 from Esbon, Kansas, and taught in one room school houses as the sole teacher for children first through twelfth grades in the Idalia and Joes area. Bob (Robert) Benton ended up in Joes after WWI pursuing a mail carrier job. They met, were married in 1921 and settled in Joes permanently in 1926.

The collaborating artistic team of Jacques Abelman, Maureen Hearty and Kirsten Stoltz worked to create the Prairie Futures artwork over the course of one-year, one overwhelmingly tenuous due to covid-19 scares. Questions about safety, isolation, community dynamics, and depression all found their way into the creative process. Without being in the same room they built from creativity’s fragments qualities essential to the project— social support and a sustained art and agricultural experience for Northeastern Colorado. Navigating through fields, both literally and metaphorically, their vision breaks habitual views of art based around singular creative engagement, instead they built an interconnected land art site uncommon and unseen in rural Colorado.

The Prairie Futures project displaces dirt, knowledge and memory to form a critical mediation on human and nature’s co-existence. The sparseness of the artwork in this landscape is inspired by the complexities of Joes, specifically, its future environmental catastrophes and the regional entropic realities of small towns. It is located on a crumbling multi-generational homestead, a couple doors down from the abandoned Alma Motel, off the two-lane highway 36 overrun by semi trucks full of plastic storage bins. The earnest intention of this artwork is that it will form attachments, and invite strangers without long histories or memories to recall this place and build more inclusive alliances. These visitors will begin to understand Joes’ complicated history, seek protection for this land, and imagine new partnerships with their rural neighbors, because when fostering new social connections, it changes arts’ experience and transmits its value into the future.

The Future We Are Making

The community organizing vision for the Liberty Rural Learning Cooperative’s project, Prairie Futures, brings as broad a spectrum of voices together as possible to address the problem of the impending eradication of eastern plains agriculture and communities due to the impending water crisis. Water shortages are not just farmers’ problems; depleted water equals depleted property values, schools, infrastructure, employment, family and of course, food. Water use and conservation is an issue that should connect us all because its impact certainly does.

When this project was taken on, the aim was to bring to the table as many people from as many sectors as possible: non-profits, businesses, schools, government, health care providers, student organizations, scholars, etc. The idea of diversity takes on a different shade in a mostly-white, mostly-Christian population whose aggregate political ideology puts a premium on surviving with as little outside help as can humanly be managed.

Community-organizing in rural Northeastern Colorado can be difficult, due to the simple and tautological fact that there are not very many people in rural areas. The dearth of humans leads to an inevitable scarcity of the financial and physical resources (not to mention the moral-support) that are so essential to any sort of ambitious endeavor. The few people who are actively engaged in the community often find themselves bearing an overabundance of responsibility as a rotating cast of board-members and cheerleaders for everything from the school board to the phone board to the FFA council to the volunteer fire department to the volunteer ambulance service, and so on.

Turns out, an isolated community of isolated people can host a remarkable variety of thought, expertise, and enthusiasm. When these qualities are brought together and given the right amount of direction (that is, as much as possible, as indirectly as possible), it’s a marvel to see just how quickly and eagerly folks can dive into something as flat-out strange as a fluxus-inspired garden of unconventional crops meant to draw attention to the dwindling supply of water in the unbelievably-precious Ogallala aquifer, which has been feeding thousands of acres of corn, which has been feeding millions of head of cattle for dozens of years. And yet, from weakness is derived strength; the folks who do get involved are incredibly capable, resourceful and adaptive problem-solvers with access to a dazzling variety of heavy machinery, and know-how.

The Panoramic Outlook

The Prairie Futures site is a living organism that has the potential to change over time. Locally, citizens are asked to reimagine new ways of supporting practices—both artistic and agricultural—that oftentimes have been excluded from conversations about climate change urgency, collaborative potential, and progressive resources.

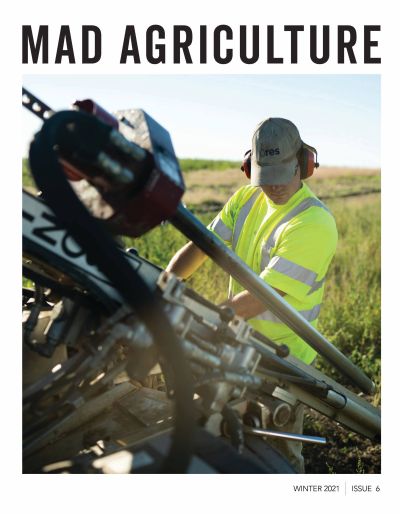

A companion farmer-in-residence program has been integrated into the Prairie Futures’ project. This allows the group to identify regional stakeholders and build opportunities for creativity to be rewarded. A farmer is paid to experiment on small crop production and investigate food sources that complement today’s soil health, water conservation efforts and regenerative-ag possibilities found in the High Plains region. Co-produced with a regional FFA school program, the gardening program provides vital experiential learning and allows for alternative landscape reimagining to happen.

Annual programs, reflective of the seasonal cycle of growth, provide opportunities to engage new audiences and participants. Prairie Futures was created with one goal in mind—build better bridges between rural and urban populations through education and art, inviting farmers and artists to make a concerted effort toward living harmoniously within a place. Visiting this site is about reimagining coexistence and finding beauty, life and hope in the vast prairie sea.

The Prairie Sea Projects is an art initiative that builds across disciplines and imagines new space for rural communities to thrive. https://prairieseaprojects.org/