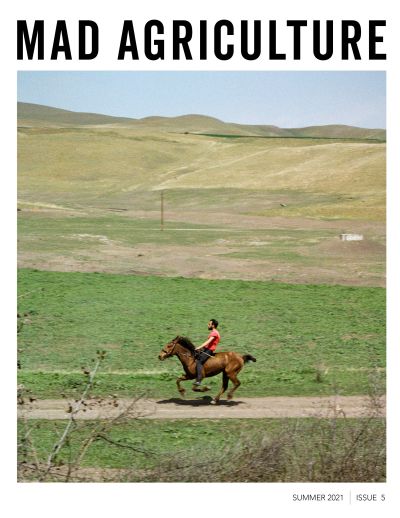

The Mad Agriculture Journal

Issue 5. Letter from the Editor

Published on

June 08, 2021

Written by

Philip Taylor

Photos by

Arina Abbott

Lee esto en español.

Dear Reader,

One of the great disasters of colonization is the loss of story, memory, and the ensuing trauma of broken relationships that leave wounds open or create scars that become hard to see, and even more difficult to heal. Living roughshod in a place disorients history, and creates a blindness to the past that unhinges our responsibility and accountability to what people and place need us to be for equity and beauty to thrive.

I’ve lived in Colorado for 13 years and confess that I hardly know the place. As an ecologist and general lover of place, I find it remarkable how much I feel like a fish out of water, despite my intentionality in being here. In short, I’m learning that it takes generations to discover and live in right relationship. And it’s not up to me to decide, but requires a communal effort that creates and relies on story, song, ritual, observation, tending, experimentation and more, which must evolve over time.

Many of us have trail-blazed across sea, country and culture, without developing a firm tether to the places and people we depend upon. For me, this behavior stems from colonization and the notion that there is more freedom and opportunity beyond the place I currently am. I’ve moved around the country in pursuit of professional aspirations and curiosity of the West. Whether my meanderings are ‘good’ or ‘bad’ is for another debate. Through it all, I have noticed that in moving there is a danger of further disconnection from the natural world. I think this occurs at the personal and civilization scale. It is easy to live almost wholly within the artificial systems we’ve created to buffer ourselves against being in nature. Our enjoyment of nature often reduces to exercise, yoga or hiking, and other cerebral efforts, like thinking about how driving cars and climate change might influence snowpack or conflicts in Africa.

It is rare for people to know the soil, birds, algae, lichen and the intricacies of ecosystems we live and breath in. We lose more than we can appreciate when we uproot, abandoning deeper stories for the sake of progress, and rarely return to the act of understanding our place, which takes time, patience, curiosity and lots of questioning.

I’ve been learning that story is the foundation of wise existence. As Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estes writes, ‘Story is far older than art and science, and will always be the elder in the equation no matter how much time passes.’ If I’ve learned anything in the past year, it is the importance of listening to elders and those we cannot often see because of privilege. There are many types of stories. Over the past few years I’ve been drawn to the stories of my non-human neighbors hurt by agriculture.

Agriculture is currently the most destructive force on the planet, and stands as the greatest driver of climate change, biodiversity loss, habitat destruction, soil erosion, labor injustice and so much more. If we hope to heal our relationship to Earth, we must begin with agriculture, the nexus point between human and planetary health. I think we need to begin with the stories of the things we’ve trampled, exterminated and displaced, which I explore in my essay Animal Hats.

A dear friend recently handed me a small book by Albert Schweitzer, a remarkable polymath that won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1956. He calls for a boundless ethic of compassion and care for all living things based in Reverence for Life;

“Profound love demand a deep conception and out of this develops reverence for the mystery of life. It brings us close to all beings. To the poorest and smallest, as well as all others. We recite the idea that man ‘master of other creatures,’ ‘lord’ above all others. We bow to reality. We no longer say that there are meaningless existences with which we can deal as we please. We recognize that all existence is a mystery, like our own existence. The poor fly which we would like to kill with our hands has come into existence like ourselves. It knows anxiety, it knows hopeful happiness, it knows fear of not existing anymore. Has any so far been to create a fly? That is why our neighbor is not only man: my neighbor is a creature like myself, subject to the same joys, the seam fears, and the idea of Reverence for Life gives us something more profound and mightier than the idea of humanisms. It includes all living beings.”

Albert calls us to an ethic that sees all living things as neighbors, and asks us to found our relationships on a more expansive love. This idea is powerful because we cherish what we love. We fight, defend and protect for what we love. We care for what we love.

Loving isn’t always convenient. In fact, loving is hard work. Love is a matter of choice. It requires attention, vulnerability, commitment, and doing things that you don’t want to do. Humans have forgotten what is most important to love. We must not withdraw from the realms of suffering, but rather lean toward it.

How can we protect, preserve, steward and heal what we do not understand? How do we care for what we do not know? How do we look back and forward at the same time, given where we are?

I think it would be fruitful to first remember what has been lost, and hopefully, in our collective remembering we begin to construct a boundless ethic that seeks equity for all. This process begins with observing, listening and sharing what we find. In this journal, I share a few stories of the species I’ve connected with, and who have shaped my life. I encourage you to do the same. I honor them, their stories and their place, as fellow neighbors on planet Earth.

Madly,

Phil